School Holiday Sampling: A Case Study of Community Engagement in Research

How community, youth and hapū engagement was successfully embedded into Faecal Source Tracking research, part of the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge.

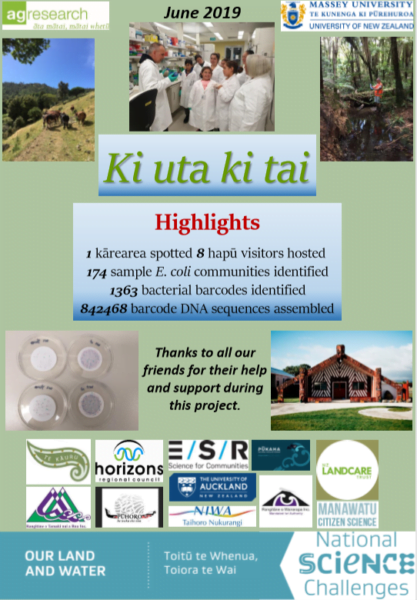

The Faecal Source Tracking project used DNA sequencing to identify 23 strains of ‘naturalised’ Escherichia coli that are not associated with risk to human health, unlike other faecal strains contaminating waterways. This work is a significant contribution to the evidence base contributing to New Zealand’s water quality standards for “swimmability”. The two-year project wrapped up with an end-of-project community hui on Wednesday 12 June. The project was a collaboration between AgResearch, Massey University, NIWA and ESR, with community and iwi involvement. It was funded by the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge and AgResearch SSI Funding.

Adrian Cookson, leader of the project and AgResearch senior scientist, shares how he embedded community, youth and hapū engagement in this research:

We knew before the Faecal Source Tracking project began that we wanted to integrate Māori engagement and mātauranga throughout our research. Fortunately, before we started we’d heard there was interest regarding water quality from an iwi from Dannevirke, Rangitāne o Tamaki nui a Rua, about an hour’s drive from where we are, through the Manawatu Gorge. The Mākirikiri Reserve, at the confluence of the Mangatera River and Mākirikiri Stream, had recently been returned to the iwi as part of a Tiriti settlement.

At the same time, we approached an environmental group, Te Kāuru, a collective of hapū from the Eastern Manawatu River catchments, that was very active with riparian planting in an effort to improve water quality.

We also discussed our project with Horizons Regional Council, as we were interested in taking samples from sites with historical data and ultimately, assisting regional councils with improved methods for establishing water quality. The Horizons Regional Council samples the Mangatera River monthly as part of its ‘State of the Environment’ sampling initiative.

To create the initial engagement, we invited representatives from Rangitāne o Tamaki nui a Rua, Te Kāuru and Horizons to our first meeting, to decide on sampling sites that would tick all the boxes. It was crucial to bring in iwi partners right from the start; from there, we got to a shared vision and principles, and developed mutual respect.

Throughout the programme, we’ve maintained an ongoing dialogue with the community. The important thing was that we started engagement very early

Teachers and students at the kura (school) near the Mākirikiri Reserve were also interested in the health of the waterways running through the reserve, and were keen to integrate Māori cultural health indicators in an analysis of the waterways. We always had the intention to bring some of the school children from the kura to the lab, but it was very tricky to get that part of the research aligned with the kura curriculum.

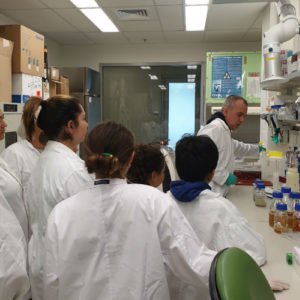

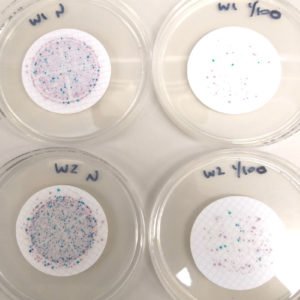

Eventually a 3-day school holiday programme was put together, and in April 2019 we went out and did sampling with 6 or 7 school kids and a few parents. The next day they came over to Palmerston North to the Hopkirk Institute Laboratories, so they could see how we processed samples taken the day before, and how we interpret results to obtain E. coli counts from the various samples we’d taken. It was the first time for most of them to see what goes on in a lab, wear a lab coat and see bacterial colonies on filters growing on agar plates.

Earlier in the research, a huge highlight had been having two interns, Ella and Meschka, from the Pūhoro STEM Academy in the lab for a week, taking samples and doing analysis, giving them a flavour of what it’s like to be a researcher. The Pūhoro initiative provides Māori high school students with mentoring, tutoring and field trips to reach their potential and navigate career pathways into science and technology-related industries. Methods for water quality assessments seemed a great example of integrating our research with the Pūhoro programme, highlighting the cultural aspects of water as taonga and tools to measure E. coli in partnership with motivated Pūhoro students.

Throughout the programme, we’ve maintained an ongoing dialogue with the community. The important thing was that we started engagement very early – the first time we sampled we had some of the hapū come with us to watch what we were doing – and we’ve continued that through subsequent hui at the end of every year where we update everybody with progress.

We’ve also done a few very simple email updates, mainly a single A4 PDF with a load of pictures and 3-4 lines of science or engagement highlights. That’s been a great way to provide a very brief update and maintain that linkage.

We’ve also done a few very simple email updates, mainly a single A4 PDF with a load of pictures and 3-4 lines of science or engagement highlights. That’s been a great way to provide a very brief update and maintain that linkage.

The end-of-project hui is to share some research and relationship highlights, and provide some indications of how the work can move forward. I’m hoping to create a framework to continue the relationship by continuing to sample at those sites.

I’ve never engaged different communities, youth or hapū in research in this way before, but I found that all participants could connect from the perspective of trying to make environmental gains and understand what’s happening with water quality. The iwi representatives were very understanding of my minimal te reo abilities – the shared vision was more important than the language you use to articulate it.

The next step for this research is to take a more national approach and undertake sampling elsewhere in New Zealand. It will be great if we can build on our engagement approach in this project to engage with iwi at sites we may want to sample at, in other locations. The ultimate aim is to develop a straightforward test that can differentiate between naturalised and faecal E. coli, perhaps allowing a small percentage of rivers that are currently classified as non-swimmable to be safely reclassified.

—

For more on this research project, see:

Author

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024