How Much Difference Has Good Farm Management Made?

Our rivers would be in much worse condition today if farmers had not adopted better practices over the past 20 years, finds new research from the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge that measured the impact of farmer actions. Plus: The best-case scenario for 2035. Download a short, plain language Research Findings Brief about this research.

Farmers have been taking action to improve water quality for years. Despite much hard work and investment, some New Zealand rivers still aren’t meeting community expectations for purity, swimmability and mahinga kai (food and resources).

It’s a discouraging and thankless situation for land managers, who know how much effort they and their neighbours have made, and yet have no way to measure the overall impact of their work on New Zealand’s water quality.

Meanwhile, the dairy sector has expanded significantly, with a 40% increase in dairy-farmed land making it even more difficult to connect improvements in land management with changes in water quality.

Our Land and Water, one of 11 National Science Challenges that fund research aimed at solving New Zealand’s biggest problems, recently investigated the impact on water quality of adopting better practices on dairy, sheep and beef farms.

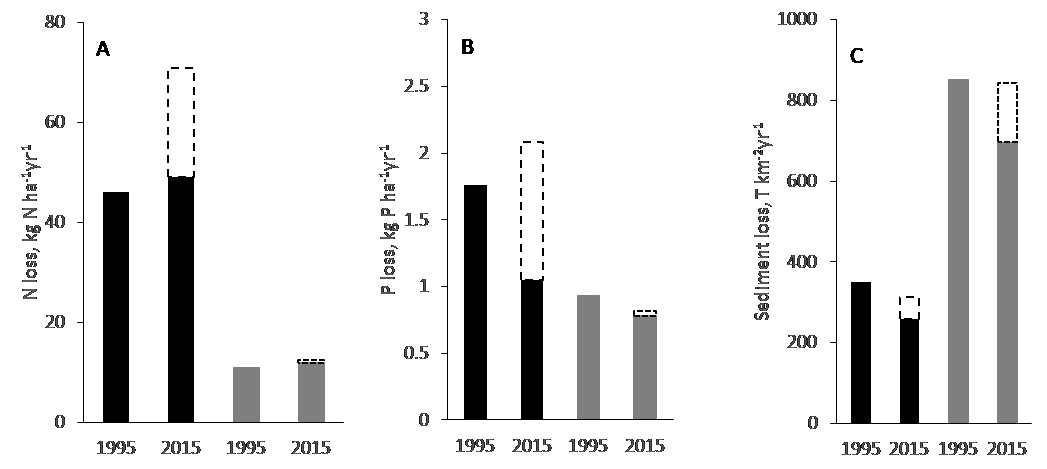

The researchers wanted to understand how effective on-farm mitigations have been so far, by comparing losses of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and sediment in 1995 and 2015, and what would be possible for future water quality in 2035 if every farm in New Zealand adopted every known mitigation.

This information is crucial to helping farmers in degraded catchments decide whether to continue investing in mitigation actions or consider making changes to land use or land-use intensity.

“When we look at adopting all the established mitigations that we have now, most New Zealand catchments can get most of the way towards meeting the current water quality objectives,” says Professor Richard McDowell, chief scientist at Our Land and Water.

“We've got plenty of work we can do with the stuff we know now, so let’s get on and give it a go.”

Four key research findings

- The results showed that our rivers would be in much worse condition today if farmers had not adopted better practises between 1995 and 2015.

- Significantly more nitrogen (45% more) and phosphorus (98% more) would have entered rivers from dairy-farmed land between 1995 and 2015 if farmers had not adopted better practises. The most effective N and P mitigation practices used over the period were stock exclusion, improved effluent management and improved irrigation practices.

- On sheep and beef farmed land, 30% more sediment would have entered rivers between 1995 and 2015 if farmers had not adopted better practises. The most effective sediment mitigation practices used over the period were planting more trees, excluding stock from waterways, and soil conservation works.

- If all known and developing mitigation actions were implemented by all dairy and sheep and beef farmers by 2035, potential loads of nitrogen and phosphorus entering rivers might decrease by one-third, and sediment by two-thirds, compared to 2015. For many catchments, this will be enough to meet current water quality objectives.

We've summarised the findings of this analysis into a short Research Findings Brief:

Why isn’t water quality better?

Despite the efforts of many farmers to care for our water, at the same time on other farms land use changed and farming intensified.

Land area used by dairy expanded 40% between 1995 and 2015, and together with changes on farm such as increased fertiliser use, total dairy production increased by around 160%. The land area occupied by sheep and beef contracted, but the intensity of production per hectare increased.

This increased food production continued to put pressure on freshwater by increasing total nitrogen loss. Mitigations were not sufficient to offset these increased nitrogen loads.

What did the researchers do?

Our Land and Water pulled together a team to do a national-scale assessment of the effectiveness of mitigation actions. The Sources and Flows research programme estimated nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and sediment losses in 2015, and compared these to scenarios including:

- 2015, assuming the practices of 1995 were still in use (“2015 past”)

- 2035, assuming the full implementation of all regularly used and developing actions

The researchers combined data on geographic and mitigation efficacy to model the total losses of N, P and sediment for around 130 farm typologies, which considered landscape attributes (such as soil, topography and climate factors) and land use pressures (such as farm inputs and feed and stock management practices) that influence contaminant transport to water.

The effect of on-farm mitigations 1995–2015

On average over Aotearoa between 1995 and 2015:

- Dairy N losses increased from 46 to 49 kg N/ha/yr – but would have increased to ~72 kg N/ha/yr if farmers had not adopted better practices.

- Dairy P losses decreased from 1.7 to ~1 kg P/ha/yr – but would have increased to 2.1 kg P/ha/yr if farmers had not adopted better practices.

- Dairy sediment losses decreased from 350 T/km2/yr to 260 T/km2/yr – but would have decreased to about 320 T/ha/yr if farmers had not adopted better practices.

- Sheep and beef N losses increased from about 11 to 13 kg N/ha/yr – but would have increased to 14 kg N/ha/yr if farmers had not adopted better practices.

- Sheep and beef P losses decreased from 0.9 to 0.75 kg P/ha/yr – but would have decreased to 0.8 kg P/ha/yr if farmers had not adopted better practices.

- Sheep and beef sediment losses decreased from 840 T/km2/yr to about 700 T/km2/yr – a similar decrease to that expected if farmers had not adopted better practices.

Note: Despite lower per hectare emissions, sheep and beef accounts for about three-quarters of national N, P and sediment losses, because much more land is in sheep and beef (8.3 million hectares) than dairy (2.3 million hectares).

“Most New Zealand catchments can get most of the way towards meeting the current water quality objectives” – Professor Richard McDowell

Best-case scenario for 2035

Putting mitigations into action takes time, knowledge and money. Not all farmers were able to adopt all known mitigations between 1995 and 2015 – but what if this is achieved in future?

Knowing how important our rivers and lakes are to all New Zealanders, land stewards need to know where community expectations for water quality can be met through improvements in farm practice – and where current land uses may be unsuitable.

What is the absolute best-case scenario for water quality in 2035, through improvement in farm practice alone? Researchers estimated that if all known and developing mitigation actions could be implemented by all dairy and sheep and beef farmers, the potential load of contaminant entering rivers would decrease by 34% (nitrogen), 36% (phosphorus) and 66% (sediment).

For many catchments, this will be enough to meet current water quality objectives.

For other catchments, applying all known and emerging mitigations may be less pragmatic than some change in land use or land use intensity. Additional research from Our Land and Water has enabled the identification of where this is likely to be the case; see the interactive map, Total nitrogen excess and reduction potential.

___

More information:

- Interactive map: Total nitrogen excess and reduction potential (short URL: tinyurl.com/OLW-map)

- Interactive table of all mitigations: Actions to Include in a Farm Environment Plan

- Under Pressure: The Lakes, Rivers and Estuaries Where Nitrogen Loads Exceed Limits

- Quantifying contaminant losses to water from pastoral land uses in New Zealand II. The effects of some farm mitigation actions over the past two decades, Ross Monaghan, Andrew Manderson, Les Basher, Raphael Spiekermann, John Dymond, Chris Smith, Hans Eikaas , Richard Muirhead, David Burger, Richard McDowell

- Research Findings Brief: Assessing the effectiveness of on-farm mitigation actions, Our Land and Water (Toitū te Whenua, Toiora te Wai) National Science Challenge 2020

- Quantifying contaminant losses to water from pastoral land uses in New Zealand III. What could be achieved by 2035? R.W. McDowell, R.M. Monaghan, L.C. Smith, A. Manderson, L Basher, D. Burger, S. Laurenson, P. Pletnyakov, Spiekermann R (New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research, 2021)

- Implications of water quality policy on land use: A case study of the approach in New Zealand R.W. McDowell, P. Pletnyakov, A. Lim and G. Salmon (Marine and Freshwater Research, October 2020)

- Nitrogen loads to New Zealand aquatic receiving environments: comparison with regulatory criteria Ton H. Snelder, Amy L. Whitehead, Caroline Fraser, Scott T. Larned & Marc Schallenberg (New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, May 2020) PDF available on request

- Research Findings Brief: Quantifying excess nitrogen loads in fresh water, Our Land and Water (Toitū te Whenua, Toiora te Wai) National Science Challenge 2020

- Sources and Flows research programme

Author

One response to “How Much Difference Has Good Farm Management Made?”

An enjoyable read. Great to see some acknowledgement re works being undertaken. Thanks. Let’s hope we can continue adoptions. Old adage it’s hard to be green when in the red.

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply