Think ‘Outside the Room’ When Collaborating with Community

Involving small groups of community members in local government decisions doesn’t mean the wider community will trust those decisions, new Our Land and Water research has found. Increasing trust may require engagement with greater numbers and diversity of residents.

Many local governments in Aotearoa New Zealand have, over the past 10 years, invited community members to collaborate on water management decisions. Giving people who’ll be affected by new rules the chance to help make those rules is seen as fair and democratic – and it seems reasonable to expect that it would also give more people confidence that decisions are effective and fair.

Past research has shown that participants in collaborative processes do report that resulting regional council decisions are better. However, surprisingly little was known about how collaborative decisions are viewed by residents who didn’t participate in the collaborative process.

New research from the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge, published in Water Alternatives in June 2020, investigated community confidence in the fairness, responsiveness and effectiveness of collaborative environmental management decisions in three New Zealand regions over six years.

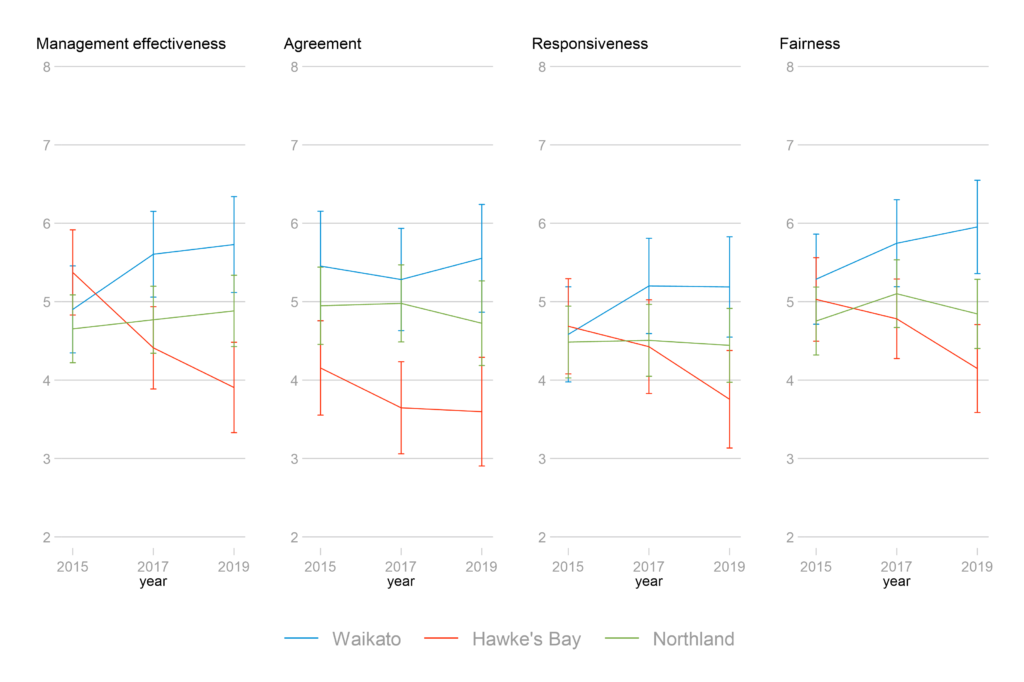

Surprisingly, the study found no indication that collaboration is improving residents’ perceptions of regional council decision-making.

Residents in collaborative catchments perceived water management decision-making to be slightly more responsive to their concerns, but no more effective or fair.

While this result may give pause to the 9 (of New Zealand’s 16) regional councils and unitary authorities who used collaboration to engage with their communities about freshwater management between 2010 and 2019, researchers are clear that this study doesn’t mean they should stop collaborating.

“There’s a risk of throwing the baby out with the bathwater,” says the paper’s lead author Marc Tadaki, environmental social scientist at the Cawthron Institute.

Collaboration may well lead to better freshwater policy and decisions, even though it won’t necessarily increase confidence in those decisions by the wider community.

“We shouldn’t think of it as a choice between collaborating and not-collaborating,” says Dr Tadaki. “Collaborative processes typically have involved getting 20 to 30 people in a room for discussion. Our research tells us this way of thinking about collaboration is too narrow. Consulting people in a room isn’t the only way to do participatory decision-making.”

How Can Collaboration be Improved?

Regional councils need to think ‘outside the room’ when undertaking collaborative processes for environmental management, says paper co-author Jim Sinner, senior coastal and freshwater scientist at the Cawthron Institute.

“One farmer can’t speak for all farmers. We need to think about who’s outside the room as much as who’s inside.”

“Our research shows you can’t take for granted that information about the collaborative process will diffuse out of that room and into the wider community. Even where it does, not everyone accepts the decisions reached inside the room.”

“It’s important to not over-rely on engaging with a limited group of community members, and instead build information transmission and ‘outside the room’ public engagement into collaborative processes.”

The research, conducted as part of Our Land and Water’s Collaboration Lab, found that residents in collaborative catchments perceived water management decision-making to be slightly more responsive to their concerns, but no more effective or fair. This tells us that more needs to be done to:

- make communities aware of collaborative processes in their catchment,

- listen to and act upon residents’ concerns,

- ensure collaboration participants are representative of and accountable to their communities, and

- broaden participation to engage under-represented groups both inside and outside the room.

Ken Taylor, former director of Our Land and Water and member of the Land and Water Forum, says most regional councils struggle to achieve wide community understanding of collaborative processes, particularly in catchments with a significant urban population.

“I’m aware of a large collaborative process that probably involved about 100 people directly, out of a total population of 54,000 of which well over half are urban. That’s a participant-to-resident ratio of 1:500. Even if each of those participants spoke about the collaborative process to 10 others, only 2% of the population would have anything more than a vague awareness that something was going on.”

There are several ways councils could encourage conversations between those ‘inside’ and outside the room, says Dr Tadaki. “One example could be a road show tour taking collaboration participants to farm days and community gatherings to build connections and listen to feedback.”

Some regional councils have made significant efforts to expand the conversation ‘outside the room’, says Dr Sinner, though it remains challenging. “We’re not saying it’s easy, just that we need to keep trying to do better.”

Regional councils need to ensure collaborative processes aren’t just another forum where elite, white and male perspectives dominate decision-making

More research on the full spectrum of participatory decision-making processes may be helpful, say the researchers, but there’s one important issue regional councils could address immediately: representation.

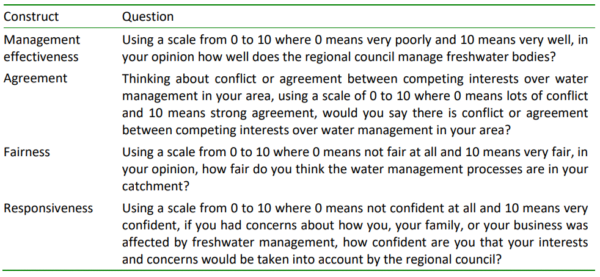

“Representation matters,” says Tadaki. “Māori and women are the least likely to be confident in regional council water management. Regional councils need to particularly gain trust with these groups, and ensure collaborative processes aren’t just another forum where elite, white and male perspectives dominate decision-making.”

How the Research was Done

The research looked at 3 regions where regional councils used collaboration to engage with communities about their values for water planning: Hawke’s Bay, Northland and Waikato. These regions initiated their intensive collaborative process between 2012 and 2014.

Phone surveys were conducted with 450 people in 2015, 2017 and 2019 to measure whether collaborative governance processes were boosting residents’ confidence in water management by regional councils (a total of 1350 survey respondents).

The research was structured to test the ‘confidence diffusion hypothesis’. This supposes that participants in collaborative processes have confidence in the resulting decisions, then will share that confidence with others in the community through personal communication, supported by media coverage and, eventually, by the community experiencing better environmental outcomes.

Based on this hypothesis, researchers expected to see community confidence in water management increase over time as outcomes became known.

Surprisingly, the researchers found that community confidence in water management did not significantly increase over time for any council.

Confidence in management effectiveness in fact significantly decreased for Hawke’s Bay residents, following a major August 2016 outbreak of gastrointestinal illness in Havelock North, caused by faecal bacterial contamination of a public water supply, which led to 5000 people becoming ill, several of whom died.

Interestingly, the people most engaged with water management issues (such as those who attend hearings) had the lowest confidence in water management, even after their regional council’s significant investment in collaborative processes. This could be caused by informed knowledge of ineffective environmental management, or it could be because those already unhappy with water management seek to become more engaged in changing it.

When looking across gender and ethnicity, significant differences were found. Non-Māori men consistently felt that water management was fairer and more responsive to their concerns compared to Māori women, who felt the least confident that water management was fair and responsive.

___

More information:

- Does collaborative governance increase public confidence in water management? Survey evidence from Aotearoa New Zealand by Marc Tadaki, Jim Sinner, Philip Stahlmann-Brown, Suzie Greenhalgh (Water Alternatives, June 2020)

- Download this summary as PDF

- The Collaboration Lab

Author

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply