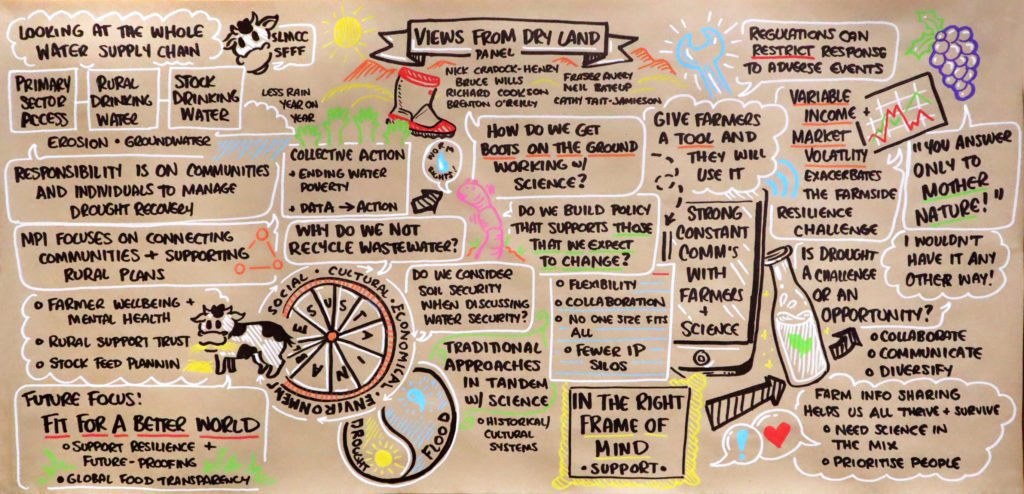

Drought: Views From Dry Land

In this panel, farmers and growers shared their lived experiences of the changing climate. They were asked how they intended to adapt to the future climate, and how others could best support their on-farm adaptation.

The following article summarises one of several symposium sessions on drought and the changing climate, part of the Growing Kai Under Increasing Dry rolling symposium held on 31 May 2021, a collaboration between the Deep South, Resilience to Nature's Challenges, and Our Land and Water National Science Challenges.

In this panel, farmers and growers from around Aotearoa New Zealand shared their lived experiences of the changing climate. They were asked how these experiences have influenced their farming practices, and how they intended to adapt to the future climate. Panelists also commented on how other agents such as government and researchers could best support their on-farm adaptation.

Panel members' individual statements have been compiled and summarised, below. While there was a high level of agreement among panelists, ideas and experiences communicated in the following discussions were not necessarily constitute a consensus.

The panel was facilitated by Nick Cradock-Henry, senior scientist with Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research where he leads work on climate change impacts, implications, adaptation and resilience to natural hazards. Nick is also co-lead for the Resilience in Practice programme in the Resilience Challenge.

Panel members were:

- Brenton O’Riley, viticulturist, Te Mata Estate in the Hawke’s Bay at Te Mata Estate. Brenton is hugely passionate about sustainability, organics, precision agriculture and the pursuit of quality wine.

- Bruce Wills, Hawke's Bay sheep & beef farmer who holds governance roles with Ravensdown, Our Land and Water, and Resilience to Nature’s Challenges, and is active within Apiculture NZ, MPI’s Deer PGP, Motu Economic & Public Policy Research, QEII National Trust and PITO.

- Cathy Tait-Jamieson (Ngai Tukorehe), BioFarm organic dairy farmer, Manawatu. Prone to drought and flood, the 250ha farm produces BioFarm yoghurt from an on-farm microprocessing plant. Cathy is the chair of her iwi incorporation dairy farm and a trustee on Te Waka Kai Ora, the Māori organic verification agency.

- Fraser Avery, sheep & beef farmer at Grassmere, Marlborough. He was Marlborough Farmer of the year in 2019, and is chair of Northern South Island Farmer Council for Beef + Lamb NZ.

- Neil Bateup, North Waikato dairy farmer with 670 Jersey cows on 240 hectares in a drought-prone area, and founding member and long-time chair of the Waikato Hauraki/Coromandel Rural Support Trust.

- Richard Cookson, Waikato dairy farmer with a PhD in soil biology and a 10-year university research career, who returned to farming 14 years ago.

Facilitator: If policy could deliver a single tool to help, what would it be?

Supporting collaboration would arguably offer the greatest benefit. Additionally, collaboration will inevitably bring together groups and individuals with different needs, and so any policy-based assistance will need to be founded on flexibility.

This need for collaboration and flexibility applies across sectors according to panelists, as do the types of tools that policy could develop and deploy. Specifically, these include new, drought-resistant cultivars, whether these are pasture, grapes, or fruit trees, for example. Policy that allows exploration of new ways to use water, from capture and storage, to minimising use and precision irrigation; regulatory flexibility was considered a useful mechanism to apply here. Investment in science was also noted as a key area for policy support so that scientists had the resources needed for cultivar development and accurate measurements.

“Every farmer is different and every farm is different.”

Facilitator: To what extent are are community trusts/support able to be nimble and responsive to people’s needs?

These trusts are about supporting people during adverse events. They are nimble and responsive, and no doubt the trusts in Canterbury would have been activated and working to support communities impacted by the current drought.

Getting farmers together and talking is the primary goal because farmers are good at sharing knowledge and learning from each other, they are incredibly adaptable and will adopt tools and technology that they can see are useful; this has been evident over recent years.

Why is this important? Because people need to be in the right frame of mind before they can make good decisions. What has become clear from supporting people who are not coping, is that they tend to be less adaptable, and may be new to the industry and without financial backing.

“In an adverse event you have to plan, review that plan, and keep making decisions. If someone’s in a good mind space, they’ll make decisions; if they’re not, decisions don’t get made.”

“Farmers who are not in a good frame of mind may not be making good decisions, or any decisions at all.”

Facilitator: In terms of helping people make decisions, can science and policy better engage with farmers and with the primary industries?

Attempts are being made to transfer science to end-users to help create impact on the ground (through the National Science Challenges, for example); despite these efforts, it remains a challenge without an easy answer.

“How can we ensure that science gets out there, is translated to impact not only policy, but also delivering effective social, cultural, environmental and economic outcomes?”

In terms of policy, when policy-makers are trying to engage, they need to understand that farmers have been adapting to adverse conditions for a long time. Dairy farmers, for example, have moved to grow feed crops in order to give themselves more control. Because there are so many things that farmers cannot control, any new tools or techniques that can increase certainty will contribute significantly to mental health.

Another change in the sector is a move to autumn calving, however, this is a double-edged sword. It has effectively shifted an environmental risk (understanding nature and how your grass grows etc) into a financial risk (growing and storing feed crops), and this has created different anxieties, particularly for farmers who do not possess the requisite expertise to manage these new practices.

Policy has to understand how farmers are adapting and what pressures they are experiencing if they are to “set the boundaries and pave the road” to support positive change.

Several panellists felt that government was not meeting this expectation currently, with farmers themselves having to take on too much individual responsibility for adaptation strategy and action.

“Policy needs to be framed a bit more around those specific issues that farmers are having.”

Facilitator: How can policy support the balance between nimble and flexible, and long-term strategic adaptation?

A theme that became apparent repeatedly during the Symposium was the need for central, regional and local government policy to be flexible rather than restrictive, as one farmer noted:b“It doesn’t support if you are regulated because you can only act within certain boundaries and this may not be applicable to the event you are facing.”

Across sectors, financial volatility is a significant moderator of how growers approach adaptation, and one that policymakers should be attuned to. Prices are determined by the export market so producers are constantly uncertain about their income, and budgeting for on-farm investment in systems and sustainability becomes incredibly difficult in this situation, which is further exacerbated by climatic unpredictability.

This economic reality is an opportunity for policy settings that can alleviate constraints and build some resilience into farmer incomes so that investment in adaptation can be confidently incorporated into planning.

“For those of you on a salary, imagine if your boss halved your salary – how would this affect how you live your life?”

Facilitator: How do we balance the financial and climatic volatility of farming with the need to maintain a long-term strategic view?

Reliable data needs to be the foundation for planning and making choices about what levers to pull and actions to take. As far as mental health goes, planning is key, and having a clear sense of one’s own purpose and values supports this.

Networking with neighbouring farmers and ensuring support systems are in place are both helpful strategies. Utilising scientific knowledge can also help by providing options and guiding choices.

While acknowledging that volatility can be a significant negative issue, several panellists said they consider unknowns to be part of the attraction to this way of life, and one that compels farmers to develop a degree of resilience.

“The joy of farming is that you pretty much only answer to Mother Nature. That’s exciting and a challenge, but we’re all eternal optimists and we always plan on next year being better.”

“When I was milking, that was my thinking time. You’d work through the challenges and look at the variables, those you could control and those you couldn’t.”

“I love the challenge – every day and every season is different.”

But in the end, farmers need to focus on what they can control. Building successful systems to deal with drought and other challenges are the way to improve control. Science can help achieve this, as can well-informed and effective policy, relationships, good communication, and good mental health.

Diversification is another approach to managing volatility. It is becoming more common across sectors, but perhaps especially amongst dairy farmers who are bringing additional activities onto their land, including beef, sheep, goats and crops. Alternatively, a farming operation may become more involved in the value chain through investing value-add processing of their produce, for example.

“Forty years ago we were supplying a dairy company, but now we have our own factory so we have control of our product from the grass right through to the consumer so we know what we’ll be getting for our milk. This is how we are mitigating financial risks.”

Different land management practices were also reported from the panel, for example, planting trees for flood protection, wind protection and rain capture.

“One size fits all doesn’t actually work because we’re all in different landscapes.”

There is huge adaptation currently happening across New Zealand on a farm-by-farm basis, but also in terms of the big picture. Arguably, there is more land use change taking place now than at any time in the past, for example, an explosion of horticulture in Hawke’s Bay, and the growth of forestry diffused around the country. These are examples of farmers adapting to climate change and monetary volatility.

“It frustrates me sometimes when I come to Wellington and talk to people who think that climate challenge and drought are new – they’re not, they’ve been around ever since farming. Good farmers take lessons and learn and adapt, and with climate change we just need to speed things up, push a bit harder.”

Facilitator: This is a very diverse group. How can collaboration help to make adaptation strategies applicable across sector and regions?

‘People and communication’ were considered key enablers of collaboration.

“When we start asking the question: ‘What value can we add by engaging with more people?’, then we’re focussed on the opportunity rather than the challenge.”

Sharing ideas through mainstream media would be helpful, but so too are one-on-one conversations at barbeques and other social events as people learn and teach differently. Sharing ideas will always be beneficial, and this applies to learning relevant science and exploring a range of on-farm activities.

“There’s no need to worry about IP because sharing my ideas doesn’t affect my income – this is different to many other industries.”

Facilitator: Should we focus on achieving incremental improvements or is transformational change needed in operating primary sector business and managing the land?

Panellists have observed a great deal of rhetoric about the need for change, from fencing off waterways to reducing nitrogen use, and these are being regulated accordingly. In order to be successful, farmers must listen to consumers – they are saying they want traceability, for example.

“The story for the consumer needs to feed into our adaptation or it will be ambulances at the bottom of the cliff.”

“Consumers want to see the journey and be part of it, come with us. That’s inspiring.”

Farmers need a plan for change, including preferred industry direction and clarity around the steps for achieving it.

“If we don’t accept that we need to change, then it will it will be ambulances at the bottom of the cliff, and we’ll be regulated.”

As a direct challenge to plant breeders and regulators, one panelist asked for new plant cultivars to be made available as on-farm tools. A drought-resistant ryegrass that produces less methane has apparently been developed recently; will this be approved for use in the future?

What might help farmers to cope with drought, meet methane targets and achieve other environmental aims? As one farmer stated categorically, “We’ll adapt if given the tools to change what we’re doing.”

More information:

- Growing Kai Under Increasing Dry report

- Webinar videos and summaries, and symposium panel discussion summaries can be found at ourlandandwater.weaveclient.site/kaiunderdry

Author

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply