Catchment Groups are Key to Our Freshwater Future

Compulsory farm plans, unless linked up within catchments, are unlikely to solve the problems facing many stressed waterways, writes Jim Sinner with co-authors Marc Tadaki, Margaret Kilvington, Ed Challies and Hirini Tane, from the New Models of Collective Responsibility programme team.

The government’s new freshwater policies are another step toward cleaning up our rivers, lakes and aquifers, yet it remains unclear how healthier waterways will actually be achieved.

A key mechanism to create change in rural areas is the requirement for virtually every farm across New Zealand to have a certified farm environment plan that describe their intended actions to improve freshwater. Farmers' actions must be audited regularly, which the government expects to generate widespread ecological improvement.

In principle, farm environment plans could be designed to suit the unique circumstances of each of New Zealand’s 30,000 or so farms and the needs of nearby waterways. But when we consider the incentives facing farmers and farm planners, there is reason for concern.

The government has yet to specify what farm environment plans must contain, but some regional council requirements suggest they will likely be based on industry definitions of ‘good management practice’ (GMP). Compared to a farm plan customised for local waterways, a GMP approach requires less analysis and time, leaves less room for argument, and is easier to get accepted by an auditor and regional council.

GMP doesn’t reflect the complexities of varied soils, weather, land use and farming practices that ultimately determine the health of waterways

The problem is that, by necessity, industry GMP is defined to suit most farms within that industry. So GMP tends to be ‘lowest common denominator’ stuff and doesn’t reflect the complexities of varied soils, weather, land use and farming practices that ultimately determine the health of waterways.

The net result is that the government’s farm plan requirement is likely to generate a low level of ambition that won’t solve the problems facing many stressed waterways, such as sediment or E. coli hot spots.

In another five or ten years (if there is any let-up at all), farmers will again be blamed for poor water quality and may be required to move their fences back and implement other one-size-fits-all rules.

If individual farm plans using GMP won’t be enough to heal our waterways, what should we do?

Our suggestion: A coordinated approach that links adjacent farm plans and focuses on outcomes. Linking farm plans can enable landowners to identify solutions unique to their soils, land use practices and waterways as well as pool resources to undertake shared works.

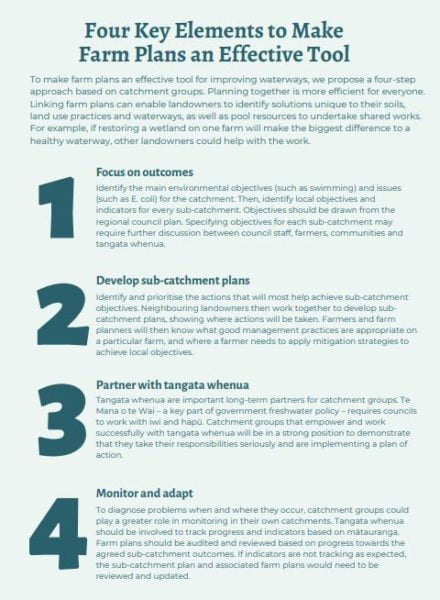

Four Key Elements to Make Farm Plans an Effective Tool

To make farm plans an effective tool for improving waterways, we propose an approach based on catchment groups, with four key elements: identify outcomes, develop sub-catchment plans, partner with tangata whenua, then monitor and adapt.

First, focus on outcomes. Identify the main environmental objectives (such as swimming) and issues (such as E. coli) for the catchment. Then, identify local objectives and indicators for every sub-catchment. Objectives should be drawn from the regional council plan, but specifying objectives for each sub-catchment may require further discussion between council staff, farmers, communities and tangata whenua.

Second, identify and prioritise the actions that will most help achieve these sub-catchment objectives. Neighbouring landowners then work together to develop sub-catchment plans, showing where actions will be taken. Farmers and farm planners will then know what parts of GMP are appropriate on a particular farm and where a farmer needs to go further to achieve local objectives.

Planning together is more efficient for everyone, because it avoids the need to implement every GMP on every farm. For example, if restoring a wetland on one farm will make the biggest difference to a healthy waterway, other landowners could help with the work.

Third, partner with and empower tangata whenua. They are in it for the long haul, and Te Mana o te Wai – a key part of the government’s policy – requires councils to work with iwi and hapū. Catchment groups that work successfully with tangata whenua will be in a strong position to demonstrate that they take their responsibilities seriously and are implementing a plan of action.

Fourth, monitor and adapt. To diagnose problems when and where they occur, catchment groups could play a greater role in monitoring in their own catchments. Tangata whenua should be involved to track progress and indicators based on mātauranga.

Once these four elements are in place, farm plans should be audited and reviewed based on progress towards the agreed sub-catchment outcomes. If indicators are not tracking as expected, the sub-catchment plan and associated farm plans would need to be reviewed and updated.

Being responsible for the health of local waterways, instead of ticking GMP boxes, will get landowners to focus on doing what is most likely to improve the waterway. This will create a positive environment that motivates everyone to play their part and will give farmers greater control over their own destiny.

___

More information:

- Printable 4-step plan for catchment groups to develop effective farm plans (PDF, 1 page)

- Guidance for farmers who are interested in joining or starting a catchment group: What You Can Do – In Your Catchment

- New Models of Collective Responsibility research involves working in four regions to support and learn alongside existing and emerging catchment groups. The research team is producing recommendations for how government, councils and the primary sector can support catchment collectives.

- Interview with Sarah's Country

Author

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply