Can Catchment Groups Foster an Ethic of Care for our Waterways?

Policy aimed at changing practices on individual farms isn't working, writes Jim Sinner from our Collective Responsibility research team. Could collective management, through catchment groups, achieve better outcomes for our waterways?

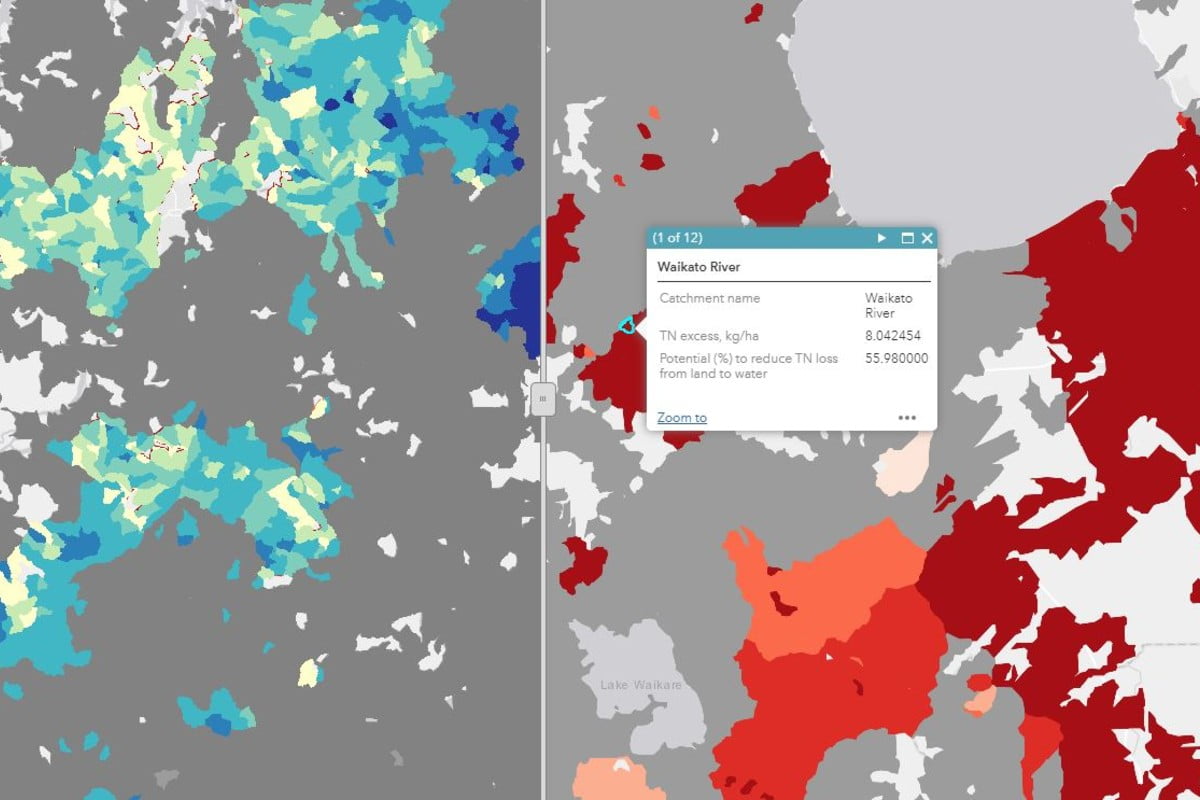

Over the past several years, I’ve had a growing sense that our policy approaches for improving freshwater health are not working and not going to work. We have cajoled, shamed, subsidised and regulated farmers and foresters to take action on their individual properties, largely ignoring the ecological reality that the health of a waterway is determined by the cumulative effects of all land within a catchment.

In some cases, we have tried to deal with cumulative effects by estimating how much of a given contaminant a waterway can cope with. For Lake Taupō, for example, shares of the total allowable nitrogen runoff were allocated to individual properties and land users are now required to operate within these allocations.

That might be appropriate in places like Lake Taupō where one contaminant is the main concern – at least for now.

Good management practices on individual properties are often insufficient to address the local, cumulative effects on a given waterway

Most of New Zealand’s rivers, lakes, streams, wetlands and aquifers are ecologically complex. We could never hope to calculate ‘sustainable limits’ of nitrogen, phosphorus, sediment, bacteria and water takes for every waterway in New Zealand. To do this well, we would have to understand how these contaminants all interact with physical habitat to affect diverse values such as mauri, mahinga kai, swimming, kayaking, wildlife, and drinking water for people and animals.

That is an impossibly complicated task, so instead, policy tends to default to rules about ‘good management practice’ – directing land users what to do on their property. These regulations need to be broadly applicable to all properties of the same type, so they are typically set at a low bar: the lowest common denominator.

As a result, the sum effect of good management practices on individual properties is often insufficient to address the local, cumulative effects on a given waterway and community. Hence we make little progress, as improved practice struggles to keep up with on-going intensification.

From an individual to a community approach

I’ve also been concerned about how the current approach, regulating each property separately, fosters a ‘tick the box’ compliance mentality.

Regulation of farming practices is seen by many land users as blunt, one-size-fits-all, and not appropriate for their situation. This stirs resentment rather than fostering an ethic of care for our waterways, for our special places and for each other.

Rather than hoping that standardised good management practices and individual property regulation will solve most problems in most places, I have wondered: could collective management – through catchment groups – build upon local knowledge and ecology to achieve better outcomes for our waterways? Would collective management help to instil an ethic of care for waterways and support for each other as neighbours?

Could collective management – through catchment groups – achieve better outcomes for our waterways?

Collective management has a long history

Collective management of natural resources is not a new idea. In many countries, communities have been collectively managing forests, fisheries and irrigation schemes for centuries. In New Zealand, there are collectively managed irrigation schemes and pest control schemes.

As Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom has shown, communities can manage their resources effectively when conditions are right:

- when users depend on the resource for their livelihood,

- when local knowledge can improve decision-making,

- when users monitor the resource and each other, and

- when social pressure is used to encourage compliance with group rules.

Waterways (streams, rivers, aquifers) are sometimes collectively managed as irrigation resources, but collective management for ecosystem health is different.

In particular, the effects of water use and runoff go far beyond those who are directly benefiting from land and water use. So we cannot rely on users’ self-interest to motivate protection of waterways, especially when the effects of individual use are largely invisible, only becoming apparent downstream (Amblard, 2019; Knook et al., 2020).

That’s a key reason why we’ve seen the health of our waterways decline steadily over the past 50 years (Ministry for the Environment, 2020).

Collective management – a new opportunity?

Through public pressure and legislative changes, tangata whenua and the wider community have made it clear that we must do better for our waterways.

The National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 (NPS) has formalised this through 22 attributes (i.e. water quality standards) and through the principles of Te Mana o Te Wai, alongside new regulations on winter grazing, fertilizer use, wetlands, fish passage and excluding stock from waterways.

Now, regional councils must develop or change plans to give effect to the latest version of the NPS, including identifying specific outcomes for every water body, and how they will be achieved.

The question is, how we will achieve these outcomes. Will we use the same approach as before, focusing on actions by individual land users? Or do catchment groups offer a better way to improve freshwater health, deliver on Te Mana o Te Wai, and build stronger communities?

What can be done now?

In a previous article, our research team argued that catchment groups offer a better way. We suggested four actions for catchment groups wanting to improve freshwater:

- identify specific objectives for each sub-catchment,

- prepare a sub-catchment plan that identifies priority actions,

- partner with tangata whenua, and

- monitor and adapt plans over time.

Now, given that regional councils are meant to identify outcomes for each waterway and set targets for 22 attributes, should catchment groups wait for this to happen before developing local outcomes and action plans at sub-catchment scales? That could take several years, during which valuable time would be lost.

Connect with Councils and tangata whenua

Regional councils and tangata whenua already have a lot of understanding and information on most waterways in New Zealand.

Councils can advise catchment groups on how the current health of waterways compares with the NPS standards, what the main stressors or problems are, and the type of actions that are most likely to improve the health of waterways.

While we should aim to improve all attributes, the attributes that are most stressed are likely to be what needs to be addressed first to improve ecosystem health and other values.

Tangata whenua often bring a different perspective and specific objectives, reflecting their history with the land and waterways. Tangata whenua have local mātauranga (knowledge) about how the river behaves (e.g., in floods or droughts), about treasured species, and about the location of wāhi tāpu (sacred sites) that warrant special protection.

Tangata whenua also bring a sense of the waterway as a whole entity – mountains to the sea – and awareness of what is important to them, such as mahinga kai and native species. This perspective is a useful counterpoint to reductionist approaches that focus on individual attributes.

Identify what matters most

Ultimately, what matters is not the concentration of nitrogen or how much sediment there is on the streambed, but whether the waterway is itself healthy and is a healthy place for aquatic life and for humans.

It is also important to look downstream, beyond the sub-catchment, and make sure a tributary is not contributing to the degradation of lakes, estuaries or the coastal environment.

Drawing upon attributes in the NPS and discussions with regional council staff and tangata whenua, catchment groups can identify interim outcomes and objectives for their waterways, without waiting for finalisation of formal regional plans.

Outcomes should be based on the key values to be maintained or enhanced in the catchment, and be something that everyone can be proud of, such as protection of a rare or threatened species, a popular swimming spot, or a site of historical and cultural significance.

Good relationships are a great place to start

This approach will also be a good start to giving effect to Te Mana o Te Wai, which requires putting the health of waterways ahead of human uses. What this means in practice needs to be worked out with tangata whenua and community in each place, so developing good relationships between land managers and tangata whenua is a great place to start.

At a recent Our Land and Water webinar, Kēpa Morgan commented: “Iwi and Hapū are most concerned with how genuine the relationship is and the intentions of forming it… Best is to visit the local marae and establish a relationship that is not outcome-driven, but that will allow you to get to know who with and when to raise issues that concern you, and ask what the priorities for Iwi and hapū are.” (Written comment submitted at webinar on 14 December 2020.)

There is much to be gained from tangata whenua and land users getting to know and understand each other’s histories and points of view, before the issues take on a legal character through formal submissions and hearings.

Also important is for neighbouring land users to hear each other’s perspectives and consider how they could work together.

There are some catchments in New Zealand where existing mitigation options are not enough to return waterways to a healthy state – land use change will be required. In these situations, catchment groups could find it difficult to agree on an action plan to achieve the long-term objectives. Yet even here, having these early conversations helps prepare everyone for the tough decisions ahead.

Catchment groups may have a wide range of objectives – these groups don’t exist just to implement government policy. Having said that, there is an opportunity for catchment groups to address freshwater issues in a way that advances the interests of farmers and foresters, as well as tangata whenua and community interests, and puts the waterways first.

Ultimately, to support an ethic of care – for the land, waterways, and our neighbours – we need strong relationships between tangata whenua and land users.

Many questions remain about how to nurture catchment communities of care. We hope to offer more guidance over the next two years as we explore these questions in our research with farming leaders and tangata whenua in four catchments around New Zealand.

___

More information:

- New Models of Collective Responsibility research programme

- Amblard L (2019) Collective action for water quality management in agriculture: The case of drinking water source protection in France. Global Environmental Change 58: 101970

- Knook J, Dynes R, Pinxterhuis I, et al. (2020) Policy and Practice Certainty for Effective Uptake of Diffuse Pollution Practices in A Light-Touch Regulated Country. Environmental management 65(2): 243-256

- Ministry for the Environment (2020) Our Freshwater 2020: Summary

Author

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply