Caring for Community to Beat Coronavirus Echoes Indigenous Ideas of a Good Life

The Covid-19 pandemic has reminded us our own wellbeing is intimately connected to other people and our natural environment, writes Our Land and Water researcher Krushil Watene, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Massey University

PHOTO CREDIT: Suz Te Tai (Ngati Manu)

The Covid-19 pandemic has reminded us our own well-being is intimately connected to other people and our natural environment.

For many people, living in a small lockdown bubble for weeks has put a heavy strain on their mental health and relationships. For others, it’s been a chance to strengthen multi-generational ties.

Māori and Indigenous peoples elsewhere have long called for social and political transformation, including a broader approach to health that values social and cultural wellbeing of communities, rather than only the physical wellbeing of an individual.

When our Covid-19 lockdowns end, we can’t afford to stop caring about collective wellbeing. New Zealand is well positioned to show the world how this could be done, including through the New Zealand Treasury’s Living Standards Framework – but only if we listen more to Māori and other diverse voices.

Relationships are at the heart of living well

For many Indigenous peoples, good relationships are fundamental to a well-functioning society. In New Zealand, these connections are captured in Māori narratives charting our relationships with people and other parts of the natural world. The relationships are woven in a complex genealogical network.

Indigenous well-being begins where our relationships with each other and with the natural environment meet. These intersections generate responsibilities for remembering what has come before us, realising well-being today, and creating sustainable conditions for future generations.

Practices that enhance the importance of these relationships are central to Māori notions of “manaakitanga” (caring and supporting others) and “kaitiakitanga” (caretaking of the environment and people). We find these commitments and practices in communities and tribal groups across New Zealand.

Similarly, the Yawuru people of Broome in north-western Australia contend that good connections with other people and the natural environment play a central role in “mabu liyan”, living a good life.

In North America, relationships as well as the need for cooperation and justice between all beings ground the Anishinaabe good-living concept of “minobimaatisiiwin”.

In South America, reciprocity in human interactions with nature is fundamental to the Quechua people’s good living notion of “allin kawsay”.

For Indigenous peoples everywhere, navigating our complex responsibilities for people and other living things in ways that enrich our existence is fundamental.

Living standards and well-being

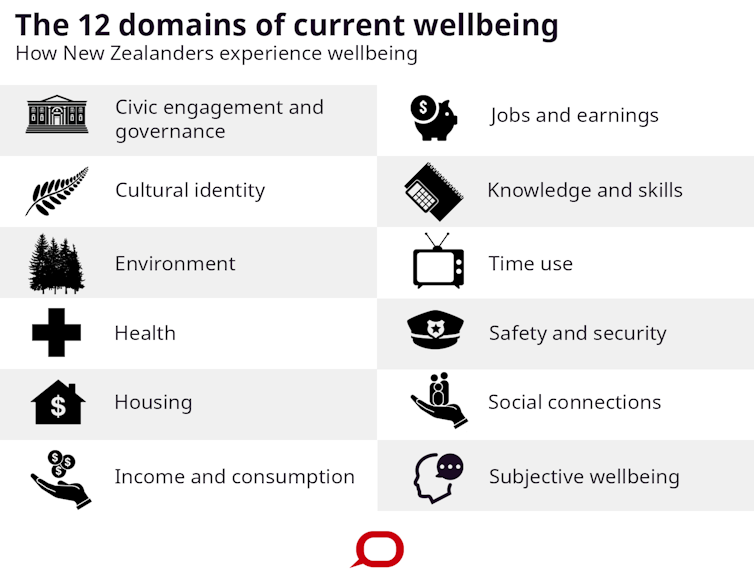

The New Zealand Treasury’s Living Standards Framework, launched in late 2018, recognises that living well consists of many dimensions, including health, housing and social connections. It is based on 12 wellbeing indicators.

Significantly, the framework has some foundation in what is known as the capability approach, which argues the focus of wellbeing should be on what people are capable of doing and what they value.

The capability approach has been pivotal in moving discussions away from measures based purely on income to a broader scope of concern: the ability to live well by relating to others and the natural environment, or by participating politically.

Indigenous peoples promote the centrality of collective wellbeing. They emphasise the importance of sustaining relationships over generations. Examples grounded in such thinking include the Māori Potential Approach, which focuses on Māori strength and success, Whānau Ora and many earlier innovations in Māori health policy. This Indigenous work is more important than ever for shaping policy to tackle inequities.

Creating a fairer future for all

When talking about New Zealand’s response to Covid-19, many people have been invoking the well-known Māori phrase He waka eke noa (we are all in this together).

But our social and political arrangements are not really equitable – and that can cost lives when it comes to a crisis like Covid-19.

Recent modelling shows the Covid-19 infection fatality rate varies by ethnicity. In New Zealand, it is around 50% higher for Māori (if age is the main factor) and more than 2.5 times that of New Zealanders of European descent if underlying health conditions are taken into account.

In the face of so many challenges – Covid-19, climate change, poverty – we have significant opportunities. One is to learn from the current experience, which has shown everyone the importance of thinking beyond individual wellbeing, to develop a wellbeing framework that better reflects diversity.

At least in its current form, New Zealand’s Living Standards Framework is missing diverse voices, especially of our most vulnerable communities such as children, older people, Māori and Pasifika communities.

Around the world, work is underway on how to develop well-being indicators for children, older people, people with disabilities, and Indigenous communities.

So too are well-being initiatives undertaken by local Māori communities. The tribal census undertaken by Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei is an example of communities committed to the aspirations of their people. To do this, we need to rethink long-standing assumptions about what well-being is and how it is measured.

Beyond this current crisis, we need to apply the same collective approach – of protecting each other to protect ourselves – to the other social and political challenges we face. By doing that, we could create a better future for all of us.![]()

___

This article by Krushil Watene is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Author

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply