Solving One Piece of the Freshwater Restoration Puzzle at a Time

How are land managers motivated to record and report their land management actions? A new paper from the Register of Land Management Actions project identifies collective engagement, efficient farm management and social norms as key drivers.

Our rivers and lakes are under pressure – and pressure is also mounting on land managers to meet new regulations and customer expectations for increasingly sustainable food production.

The good news is that farmers have been taking action, most commonly excluding stock from waterways, planting buffer strips, making riparian management plans, and constructing artificial and natural seepage wetlands.

But the devil is in the detail, and although there are a range of recognized techniques to record and report some of these actions (from paper records to photographs to digital decision-support tools), the lack of standardized recording methods means that there are large inconsistencies in how we record and report actions.

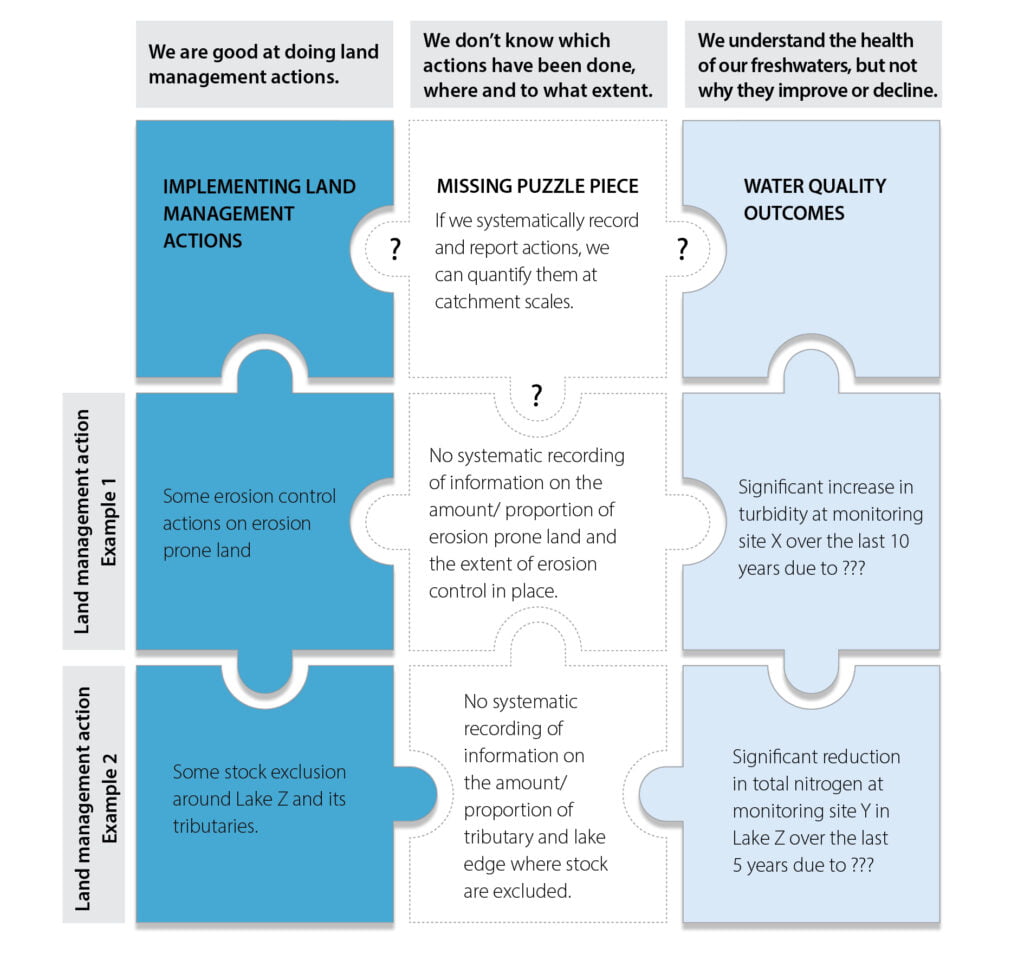

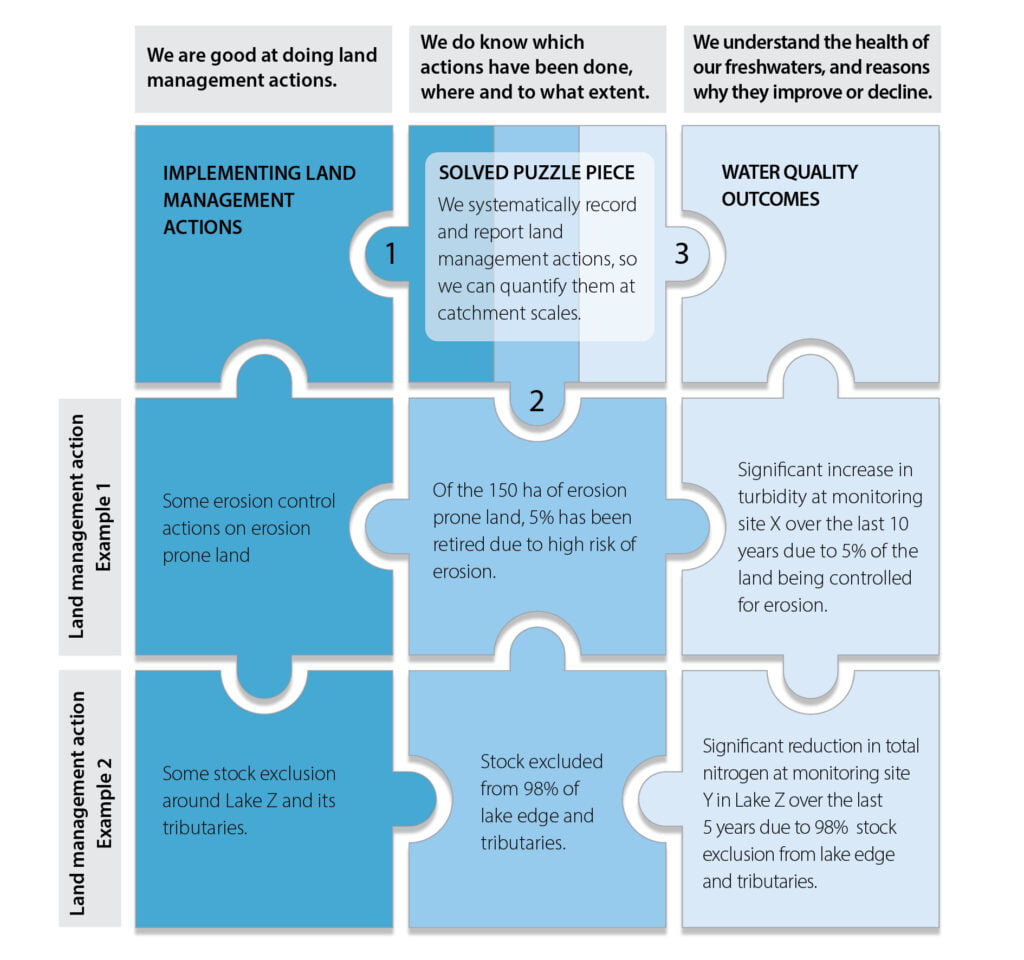

These inconsistencies result in us being unable to determine accurately which land management actions have the greatest effect on water quality outcomes, making the effectiveness of these freshwater restoration efforts difficult to assess (Figure 1).

To address this ineffectiveness, we developed a national Register of Land Management Actions which will provide a much-needed repository tool, capturing consistent information within a centralised ‘data warehouse’ that brings together data from various platform.

This information will later be presented to the public on the Land, Air, Water Aotearoa (lawa.org.nz) website.

“Any data reporting platform is only as good as the information it contains. For the purposes of catchment management, that information must be available for sharing with others”, says Kati Doehring, freshwater ecologist and science communicator at Cawthron Institute, and science delivery lead in the Register of Land Management Actions research team.

There are many aspects that decide whether we participate in something, or not, says Kati. “There is no point setting up a reporting platform if it doesn’t get used, and the knowledge shared. So, land managers must be motivated and empowered to participate in the platform, recording and sharing what actions they have done where, and to what extent.”

“We were particularly interested into the socio-psychological aspects of this, including attitude, social pressures, behavioural, cultural, economic and regulatory barriers.”

Six motivations – but 3 are crucial

The research uncovered six themes that motivated land managers to record and report: collective engagement, identity and social norms, efficient farm management, legislative, stewardship and economic.

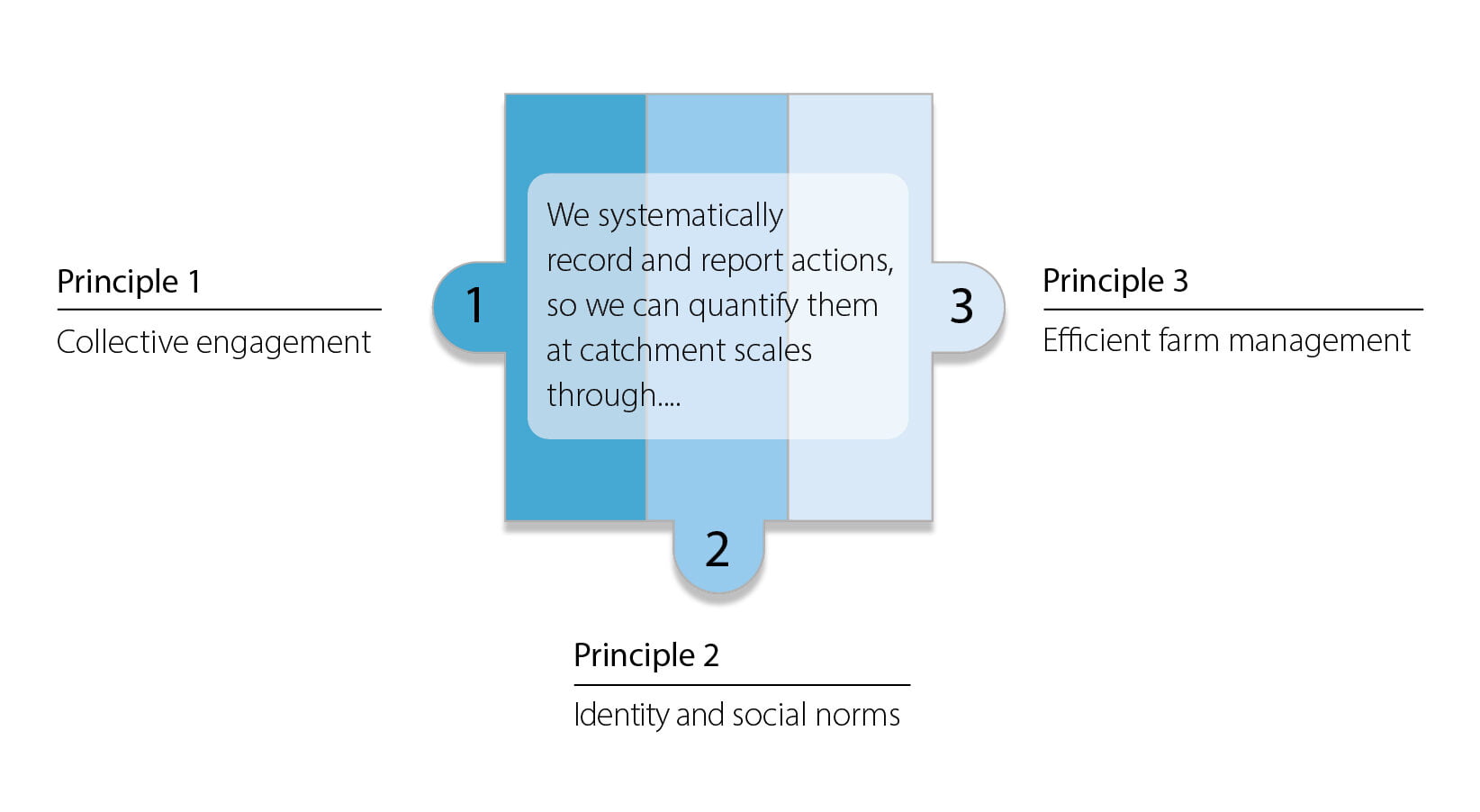

The researchers then focussed on the three themes that were most frequently mentioned by interviewees (Figure 2):

- Collective engagement: Recognising the magnitude of collaboration in a community to motivate recording and reporting.

- Identity and social norms: “Over-the-fence-mentality” motivates land managers to record and report based on what and how much others did on their farm.

- Efficient farm management: Land managers are willing to record and report if it’s made easy for them and if the actions resulted in more than just one positive outcome.

These three socio-psychological aspects should be considered during the establishment of any new on-farm environmental monitoring frameworks or policy implementations, recommend the research team (Figure 3).

“Considering all three aspects will empower farmers to adopt more holistic and effective farm management practices and bring us one step closer to linking land management actions to water quality outcomes,” says Kati. “Land managers are at the heart of this collaboration, and understanding what hinders and motivates them to record and report is essential for successful large-scale environmental management.”

How can we help reporting happen in practice?

For systematic environmental recording and reporting to be successful at large scales, five things need to happen:

- Develop standardized indicators of land management actions to allow robust assessment of change over time.

- Develop an easy-to-understand environmental recording and reporting platforms (e.g., National Register of Actions).

- Integrate new recording and reporting requirements within existing frameworks, such as industry-specific farm environment plans.

- Encourage ongoing environmental recording and reporting through holistic farm management, including stakeholders’ on-farm values (i.e., biodiversity, amenity).

- Involve ‘catchment champions’ in the knowledge-sharing process to motivate others within the community to record and report land management actions.

While these points are specifically relevant in the New Zealand context, they may be applied in other parts of the world facing similar recording and reporting challenges.

“Successfully improving freshwater quality is a complex process that requires actions from different players, at different times, and in different places, while following specific guidelines. It is like solving a puzzle, just not on your own,” says Kati.

More information:

- A missing piece of the puzzle of on-farm freshwater restoration: What motivates land managers to record and report land management actions? Katharina Doehring, Nancy Longnecker, Cathy Cole, Roger G. Young, Christina Robb. Ecology & Society, December 2022

- Register of Land Management Actions research programme

Author

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply