How Do We Measure Success? Indicators for a Better Aotearoa

The Indicators Working Group published a final summary report in September 2019. A key finding of the group is that although more data would be useful, the primary sector has enough information at its fingertips to support changing now. Here we summarise the group's key findings.

There are many ways to measure progress towards our goals as a country – but some are better than others. Choosing the best indicators is crucial when setting national targets and policy, and to enable information to be easily shared.

The Our Land and Water National Science Challenge set up the Indicators Working Group in 2017 to find the right indicators to tell us whether land uses are financially viable and environmentally sustainable, and enable and support their use.

The group's role was to support the two sectors with the highest influence on Aotearoa's environment: government (to support its international reporting requirements) and the primary sector (to help with understanding and changing land use practices).

The key finding of the Indicators Working Group is that although data is often incomplete and imperfect, we have enough current information to support changes in policy, production and marketing practices in the primary sector.

Although people and organisations would like better reporting and more data, the primary sector has enough information at its fingertips to support changing now – there is no need to wait.

What is an ‘indicator'? A relevant variable that is measurable over time or space that provides information on a larger phenomenon of interest and allows comparisons to be made.

Key reports from the Indicators Working Group

The group completed six individual projects and published 14 reports, journal articles and book chapters over a highly productive two-and-a-half years.

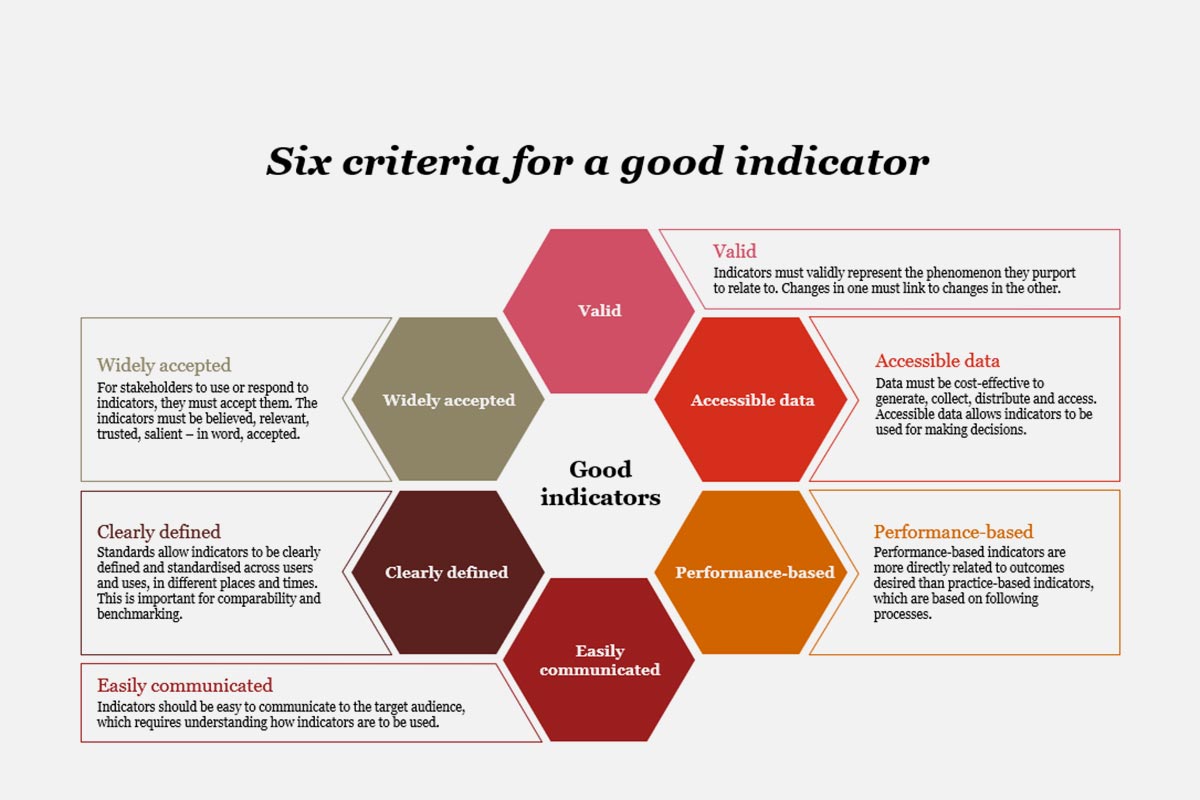

One early output proved extremely useful. The group developed six criteria to assess whether indicators are fit for purpose. These criteria for good indicators went on to form the core of many later conversations about what to measure and why, with people from government, research and the primary sector. Many indicators that were initially recommended did not meet the criteria.

Another useful piece of early work was a stocktake of indicator data in New Zealand. This work identified 28 data sets or indicator programmes that give remarkable coverage of commercial, financial and physical data that are relevant for the primary industries. It also identified inconsistencies that make it difficult for the data sets to work in harmony.

The most substantial work undertaken by the Indicators Working Group (co-funded by AgResearch) produced a method to measure community resilience at a point in time using Statistics NZ data to indicate (to a limited extent) whether rural communities are doing better or worse. Although the validity still needs to be tested on a larger sample, the results identified some highly correlated factors that influence the resilience of rural New Zealand.

The Indicators Working Group worked extensively with local and central government, industry groups, NGOs, scientists and representatives of rural communities to develop and promote the use of indicators. And their research is being used: researchers and industry organisations are using the Sustainability Dashboard and Next Generation Systems indicators with farmers. Discussions with The Treasury, Statistics NZ, MPI, NZ Institute of Primary Management, Ministry for the Environment, MBIE, Beef + Lamb NZ and individual ministers have all been informed by the Indicators Working Group.

If we keep doing things the same way, we will get the same results.

Lessons from the Indicators Working Group

Bill Kaye-Blake has been involved in all six projects completed by the Indicators Working Group. In the final report of the group, he offers some insights based on his work:

“Although there is a large amount of indicator data available, it is not centralised or harmonised. No single entity has the resources or mandate to collect and maintain economic and environment data for the primary sector.”

“A joined-up approach that produces harmonised data, available from a central source, could provide a stronger evidence base for farmers and growers, communities, researchers and government.”

A central source of data, hosted by an entity with the knowledge, resources and mandate to lead change, could improve New Zealand's economic and environmental sustainability. Until that source exists, says Bill, “The collection, curation and dissemination of data regarding New Zealand's land uses is likely to continue much as it has in the past.”

___

For more information see:

- Pointing the way: Indicators for a better Aotearoa New Zealand by Bill Kaye-Blake (summary report, September 2019)

- Indicators Working Group

- Heartland Strong: How rural New Zealand can change and thrive by Margaret Brown, Bill Kaye-Blake, Penny Payne (Massey University Press, 2019)

- Signs to look for: Criteria for developing and selecting fit for purpose indicators (October 2017)

- Stocktake of Indicator Projects (September 2017)

Author

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply