More Trees, Fewer Sheep? Incentivising Change with the ETS

New Zealand can achieve our 2050 greenhouse gas emissions targets, and keep farms economically profitable with current ETS settings – but current signals are sending us down a path towards large-scale pine forests. If that isn´t the future we want, new and innovative options and policies will be required.

Transitioning half of every sheep or beef farm to carbon forestry (radiata) would enable Aotearoa New Zealand to meet our net zero greenhouse gas emissions targets by 2050 while maintaining farm profitability, according to new modelling from Our Land and Water and Scarlatti.

One aim of the research was to provide insight for policymakers and catchment groups into which policies are likely to lead to better environmental outcomes. Understanding how farmers react to policy signals and extension support can help researchers and policy-makers improve those signals and therefore improve outcomes.

“The food system faces a significant challenge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and water pollution. We wanted to identify the policy settings and incentives that would encourage land use change, and what the environmental impacts would be,” says Kendon Bell, senior research manager at Scarlatti and project lead for Stronger Signals.

The model extends previous Our Land and Water research on how farmers react to different pieces of information (signals), to model the policy and environmental implications of that research at a local, regional, and national level.

The project modelled all current, dominant productive land in New Zealand at hectare resolution, allowing agents to choose between 19 land uses in response to external influences, and calculating the expected environmental impact of land use decisions.

Across all land uses and groups, small amounts of capability-building investment are beneficial but have limited effectiveness for meeting pollution goals. In general the drivers of change are economic.

For greenhouse gas emissions, for instance, the current ETS settings create a very large incentive for sheep and beef farmers to shift into permanent radiata forestry for carbon credits, with improved financial returns for farms.

“Achieving around a 50% conversion rate of sheep and beef land to pine forestry by 2050 is feasible in the model and would enable New Zealand to meet greenhouse gas emissions targets. This represents a transition rate of 2.8% per year, which is only slightly higher than the recent annual reduction rate of around 2% of land under sheep and beef,” says Bell.

“Achieving around a 50% conversion rate of sheep and beef land to pine forestry by 2050 is feasible in the model and would enable New Zealand to meet greenhouse gas emissions targets. This represents a transition rate of 2.8% per year, which is only slightly higher than the recent annual reduction rate of around 2% of land under sheep and beef”,” says Bell.”

Kendon Bell, senior research manager at Scarlatti

No other currently available policy settings were as economically viable, suggesting that unless we develop new, innovative options and solutions, New Zealand could be facing large scale transition to pine, even accounting for the difficulty of accurately our attachment to sheep and beef farming and resistance to exotic forestry. The current ETS costs and settings don’t support a shift to native forestry, which is more expensive to establish and generates less carbon revenue.

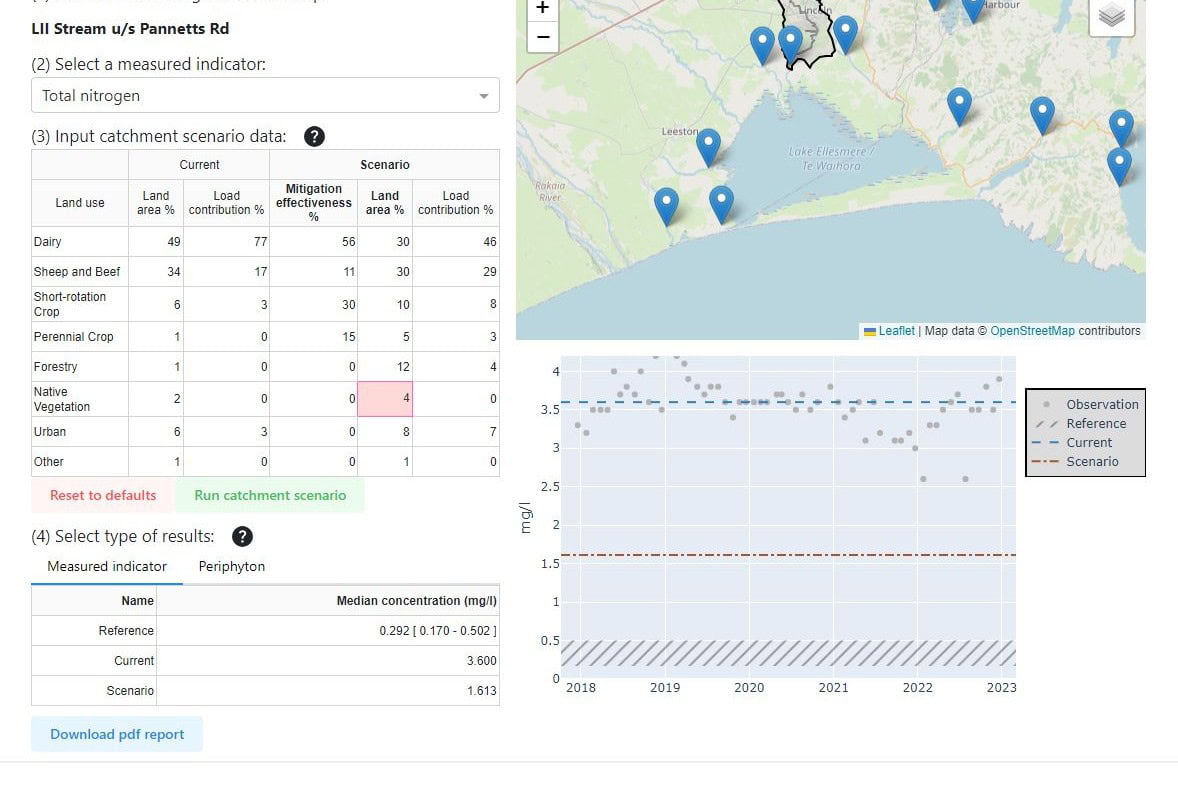

The case is similar for water quality outcomes. Targeted pollutant pricing and enforcement were found to be effective tools to achieve water quality targets for nitrogen and phosphorus, but at a substantial cost. Across Aotearoa, up to 25% of farmers in the simulation face incentive prices greater than their current operating profits, effectively forcing them to retire land into permanent forestry.

| Why pines? A white paper associated with this research provides context for research results that appear to support land conversion into pine forestry. >>Read more |

Current sediment bottom lines for water quality were also found to be unachievable in some areas, suggesting either steep costs, a change to targets, or more localised responses.

“Farmers and policymakers have long discussed the cost of achieving water quality targets, but this is the first time costs have been modelled and quantified,” says Bell. “The model goes down to hectare level, so the costs of protecting specific waterways can be directly modelled by farm or catchment, and decisions made as a community.”.

“We know what is financially viable,” says Bell. “Now it is up to communities and policy makers to decide what we want.”

More information:

Author

One response to “More Trees, Fewer Sheep? Incentivising Change with the ETS”

It would be better to use Douglas Fir and Sequoia as they are much longer lived and have more valuable timber and longer logging intervals, potential coppicing also leads to greater land stability….

Using gene editing can remove the possibility of seeding and also pollen production(better for hay fever sufferers)

Radiata and other exotic species on flatter less erosion prone land and gene editing to enhance tree growth(by gene editing out cone and pollen production) would be desirable and in smaller woodlots to minimize and break up fire risks

Long lived multi species Native trees and shrubs in gully areas that will probably never be felled or logged by helicopter would minimize sediment losses via stream flood events…

Many more trees in the landscape that provide shelter from sun and wind as small block or wind break plantings and as amenity trees both evergreen and deciduous for bird and insect habitats…

All these areas will always need pest control so that needs to be factored in at the start

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply