More Innovative, Holistic, Connected Land and Water Management Needed for Healthy Estuaries

Simply reducing the amount of contaminants entering our waterways while continuing with ‘business as usual’ land use is not enough to improve the health of our estuaries in a changing climate, new research findings suggest.

Simply reducing the amount of contaminants entering our waterways while continuing with ‘business as usual’ land use is not enough to improve the health of our estuaries in a changing climate, new research findings suggest.

Our Land and Water researchers have been looking at different land-use scenarios to see how to reduce the contaminants (soil, fertiliser, pesticides, herbicides, and animal waste) that enter our estuaries. This is part of a wider project called Healthy Estuaries Ki Uta Ki Tai in partnership with the Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge and the Ministry for the Environment.

The findings from the research imply that, from source to sea, we need to instead create more innovative, interconnected, and realistic land and water management solutions to enhance the health of our aquatic environments, as well as ensuring the sustainability of primary production.

Unique places where freshwaters meet the sea are an integral and important part of our natural environment. However, the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS-FW) does not yet have clear direction on how to account for the impacts of freshwater contaminants on estuary health. Hence, the research set out to bridge the gap between land- and sea-based issues.

Māori researchers carried out kaupapa Māori mahi with mana whenua to understand what taonga species are tohu, or indicators, of health for three case study estuaries: Kaipara in Northland, Waihī in the Bay of Plenty, and Koreti (New River) in Southland. Then, in line with the NPS-FW, Sustainable Seas marine researchers looked at whether it was possible to identify a set of contaminant thresholds.

The aim was then for Our Land and Water researchers to use these identified thresholds to model what land-use change might be needed upstream in the catchment to at least meet the thresholds – both now and in a changed climate for 2050 (mid-century) and 2100 (end-century).

Complexities come to the fore

However, the researchers found it difficult to pin down a realistic set of estuary-specific contaminant thresholds. Although the researchers found clear relationships between freshwater contaminants and the indicators of estuary health, these were not always consistent at sites within and between estuaries.

“The researchers found that the usual ways of measuring contaminant levels upstream in catchments don’t necessarily translate into how contaminants build up and affect estuaries downstream – the timings and scales of measurements are quite different,” says research programme coordinator Anne-Maree Schwarz. “For example, some indicator species such as shellfish can take years before they reflect what’s happening upstream, and we can’t wait that long to take the right actions.”

Estuaries are also less predictable and more complex than freshwater bodies, the researchers found, with factors such as distance from the sea playing a role in how ‘clean’ an estuary is. They confirmed that the health of indicators in estuaries is affected by other activities occurring within the estuaries and the effect of the ocean, not just freshwater contaminant levels.

The researchers also identified that climate change adds another level of complexity to trying to establish estuary-specific contaminant thresholds. Rising sea surface temperatures, for example, can add extra stress to estuary life already affected by contaminants.

Similarly, climate change brings more instances of heavy rainfall that will worsen erosion and therefore increase the amount of sediment in runoff entering our waterways. Earlier findings from other Our Land and Water research indicate that erosion could more than quadruple the amount of sediment in runoff by 2100 for some parts of Aotearoa. This means that the effects of climate change are likely to undo any ‘business as usual’ attempts to meet current contaminant thresholds.

Not only that, but the wildlife that live in any given estuary – including taonga species – are unique to that estuary, and each estuary’s makeup is shaped by its unique local surroundings.

This means that to try and establish a national ‘one size fits all’ contaminant threshold would not be realistic for the high diversity of all our estuaries in Aotearoa.

Modelling findings eye-opening for ‘business as usual’

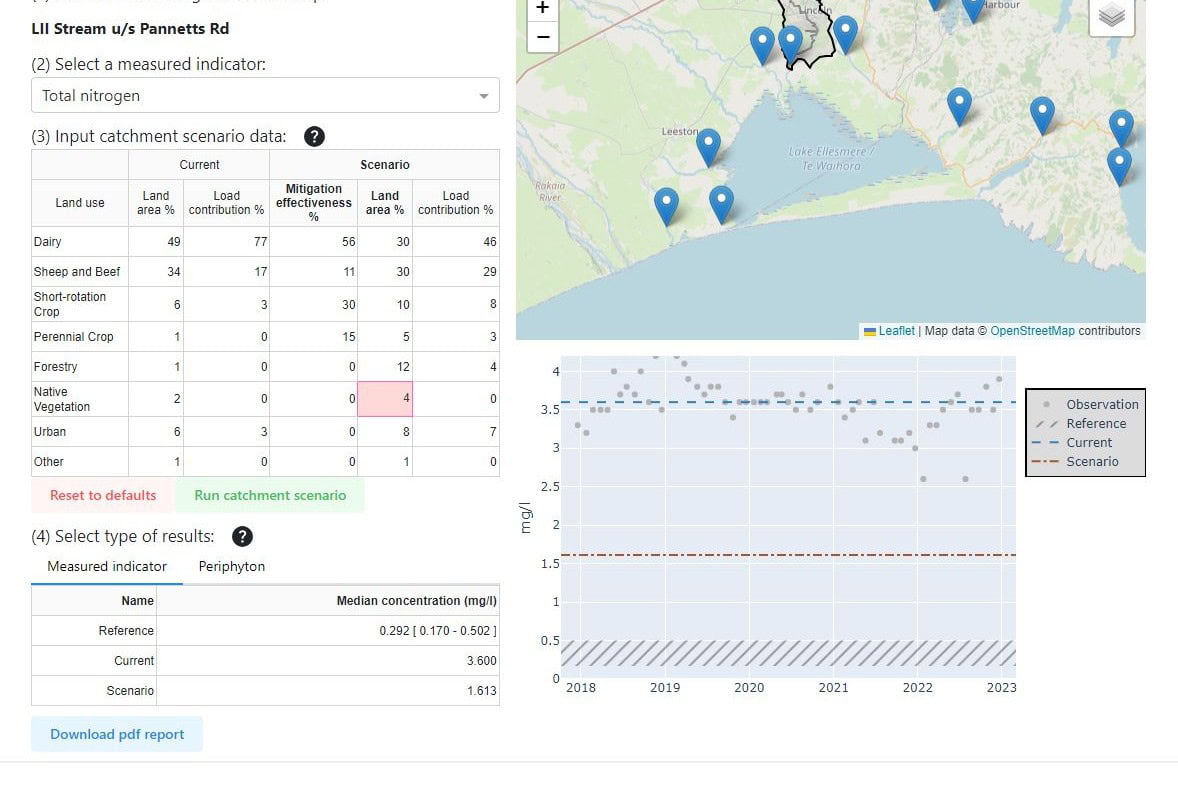

Since there were not yet any estuary-specific thresholds, Our Land and Water modellers instead used the national bottom lines for sediment, nitrogen and phosphorus, as set by the NPS-FW. This provided an initial ‘snapshot’ of how our estuaries are faring at a national level and how changes in land use might improve that.

“The modelling gave us an idea of what types of land use changes would need to happen to effectively reduce the contaminants draining into the estuaries,” says Susie McKeague, a science leader at Our Land and Water. “When the model is set to choose land uses that are profitable, the outcome is a large decrease in sheep and beef and an increase in forestry or native forest land use.”

“It found that, theoretically, we’d need to convert a large proportion of our land back to bush to get our contaminants down to a level that would ensure the health of these estuaries in the future. That is not a realistic option because to do that would severely affect the livelihood of many of our rural communities who are already working very hard to reduce their impact on the environment and need local employment.”

The types of land uses included in the modelling were limited to arable, dairy, horticulture, sheep and beef, exotic forest and natural vegetation. The researchers did not model whether advances in mixed farming – a combination of sheep and solar panels, for example – might have elicited more feasible results.

“The findings demonstrate just how much we need to start thinking outside the box in how we use our land,” explains Susie. “We need to go beyond ‘business as usual’ land use if we’re to get anywhere near where we want to be in a changed climate – environmentally as well as financially.”

| Why pines? A white paper associated with this research provides context for research results that appear to support land conversion into pine forestry. >>Read more |

Lessons for future research and policy

Although it was difficult to identify contaminant limits, the lessons still prove useful.

“We need more innovative solutions that account for and work across multiple and complex influences on estuary health, especially in the face of climate change,” says Anne-Maree.

A local, rather than national, focus could be more fruitful. The researchers found that engaging with whānau, hapū, iwi, and communities to identify local values and aspirations for specific estuaries was a more appropriate and productive approach towards restoring estuary health.

“While it is evident that we need simple tools that can be applied across all our estuaries, these need more work and will need to be able to be tailored to place,” explains Anne-Maree.

“The good news is that some regional councils are already starting to try and address this issue by creating more integrated land, water and coastal plans that aim to connect upstream and downstream areas of work that to date have been led by policies acting in silos.”

“Hopefully, this will help future researchers, ecologists and decision-makers working in this space understand that we need a much more holistic approach if we’re to succeed in restoring the health of our rivers and estuaries.”

More information:

Author

One response to “More Innovative, Holistic, Connected Land and Water Management Needed for Healthy Estuaries”

This is a very interesting article.

Our estuary in Napier, Ahuriri Estuary/Te Whanganui a Orotu, has enormous pressures from rural runoff, industrial pollution, 70% of local stormwater, intermittent sewerage discharge at times of heavy rainfall, invasive species – particularly tubeworm, and surrounding development pressures.

We are part of the myriad of local bodies, DOC, mana whenua, etc, who are ‘involved’ in attempting to improve things for the estuary. We are a spot where godwits/kuaka come each year (about 300), and other native birds, etc. It is a nursery for ocean fish. Human recreation is a constant.

You article addresses the bigger picture, which is something maybe we overlook.

We’d like to keep connected, as writing submissions is one of the things we do.

Angie Denby

Chair, Ahuriri Estuary Protection Society

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply