Lifting the Game for West Coast Wintering

With high rainfall and extreme weather events, winter on the West Coast can pose significant challenges to dairy farmers. What are the options for farmers looking to improve their environmental outcomes without breaking the bank?

The West Coast of the South Island has one of the most rugged, but beautiful, landscapes the country has to offer. Extreme weather events are common, including extended periods of continuous rainfall. These can create a challenging work environment for farmers, staff and their stock.

While the Coast is New Zealand’s wettest region, there are significant variations in temperature and rainfall as you move from north to south, says Primary Insight farm consultant Andrew Curtis.

“Pugging, resulting in sediment and pathogen run-off into waterways, is of particular concern,” says Curtis. “From a production perspective, impacts on spring pasture growth and animal welfare are also of concern.”

Stand-off pads and sacrifice paddocks are common on the Coast, but recently there has also been a lot of interest in composting shelters (or ‘mootels’) and solid-floored herd shelters.

The recent winter grazing regulations have put an increased focus on management in this high rainfall environment. Andrew Curtis and colleague Laura Bunning applied for funding through Our Land and Water’s Rural Professionals Fund to look at wintering issues for farmers on the Coast. This included an analysis of the costs, benefits and environmental outcomes for various wintering management options.

Each farm’s landscape and animal welfare risks were taken into account when selecting the modelling options

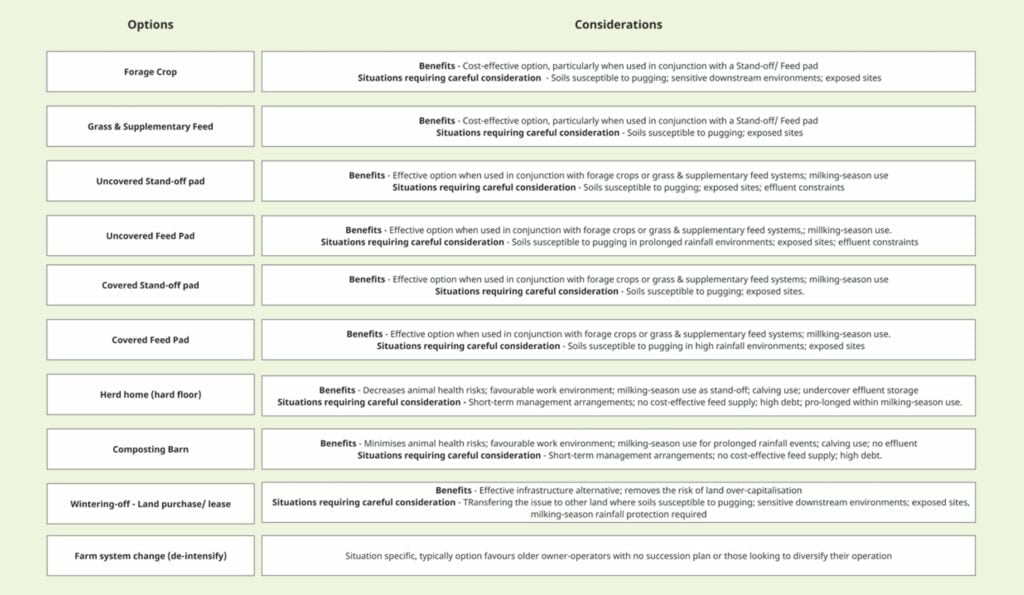

Along with looking at what options were suitable for West Coast conditions (see Table 1), they spoke to farmers with different wintering systems to better gauge the issues. They asked why individual farms had chosen their current winter management system, and what farmers would do differently if they were starting over.

Assessing the wintering options

While structures like composting shelters can have good animal welfare, environmental and pasture management outcomes, they are not a cheap option and would see most farmers heading to the bank seeking significant finance. They also need to be managed more intensely, with good access to supplementary feed.

The challenging farming conditions on the West Coast means more lower input farm systems, reflected in the lowest price per hectare of farmland anywhere in the country. This makes many farmers unwilling or unable to take on the debt required for high-cost structures. Farmers also have concerns about potentially over-capitalising their properties, especially if they are looking at selling in the short to medium term.

Farmers were keen to see how other options stacked up against the housing structures.

Three different wintering options were modelled on each of two local dairy farms. One of the farms was a system two and the other a system four.

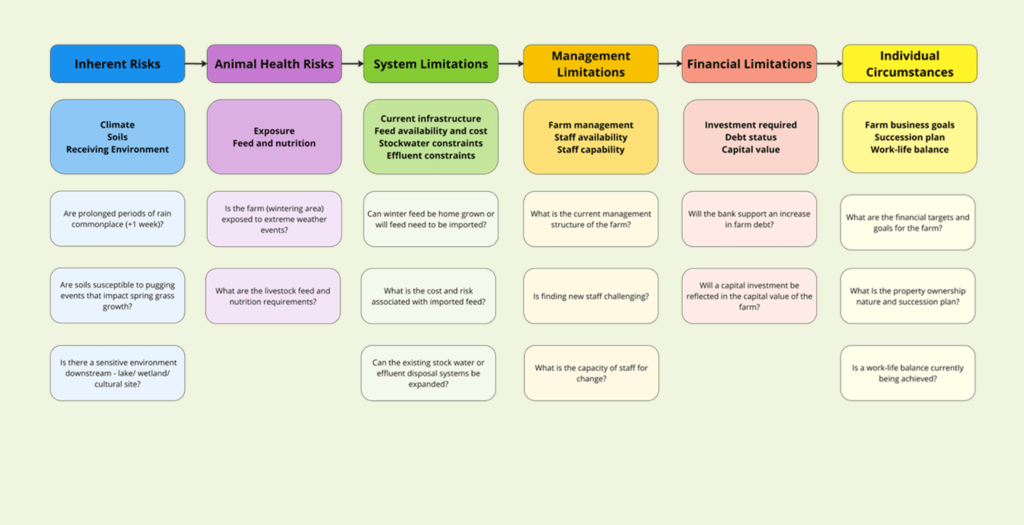

Each farm’s landscape and animal welfare risks were taken into account when selecting the modelling options, along with farm system and management limitations, farm financial constraints, and the goals of the farm owner.

The risk of nitrogen (N) loss was assessed by a simple N balance from Farmax, although it was acknowledged that OverseerFM would have provided a better estimate of N loss. “However, sediment and E. coli are also generally of bigger concern on the Coast than nitrogen,” says Curtis.

How to winter better

Why: There is little information for farmers about wintering options in high rainfall areas to improve outcomes for the environment, animal welfare and spring pasture production.

Where: Interviews with West Coast farmers running various farming systems and modelling two dairy farms on the West Coast.

Who: Laura Bunning and Andrew Curtis (Primary Insight) and eight West Coast farmers.

What:

- Interviews, workshops and farm modelling showed there is no one-size-fits-all approach to better wintering on the West Coast.

- Covered infrastructure options should be considered in higher rainfall areas, where soils are vulnerable to pugging, where there is a sensitive downstream environment, and in response to animal welfare needs.

- In some circumstances, stand-off pads or a sacrifice paddock will continue to be the best option.

- A decision-making tool was designed to help farmers narrow down the range of wintering options and develop a better understanding of their environmental and animal welfare risks, management and financial constraints and goals.

- Once key risks and limitations have been identified, a farm-specific economic and environmental analysis should be undertaken to identify the best solution.

- Farmers should avoid infrastructure investment until they have determined it is the best solution for their situation.

System two farm overview

The system two farm grew its own forage crops and maize silage, while also using palm kernel extract (PKE), and had a small feed pad in place. A lease block was used to help with wintering and raising young stock. Milking 2.2 cows/ha, the farm had an N balance of 69 kg/N/ha and an operating profit of $3,131/ha.

Three options were modelled for this farm.

- Option 1: Self-Sufficient All Grass System saw the farm drop to a system one to become a self-sufficient grass-fed system, with no imported feed or lease block. Herd size reduced as did labour and operating costs. The N balance dropped to 63 kg/N/ ha, but operating profit also dropped by 13%.

- Option 2: Forage Crops saw the maize silage crop switched to a brassica forage crop, with the remaining pasture in better shape for spring. The herd and production remained the same, but with lower production costs when compared to the current maize crop. Good feed or access to supplements for the rest of the season would be needed, along with a window for re-grassing. The N balance dropped to 64 kg/N/ha, with operating profit increasing 15%.

- Option 3: Additional Land Purchase enabled the current farm system to become completely self-sufficient. Production increased from the additional feed available to offset the interest costs on the land purchase. N dropped slightly to 66 kg/N/ha, with operating profit staying the same.

System four farm overview

On the system four farm, young stock are grazed off-farm, with the milking herd wintering on an adjoining lease block with supplementary feed (maize silage grown on-farm and PKE). A loafing pad is located near the dairy shed. Milking 2.4 cows/ha, the farm had an N balance of 98 kg/N/ha and an operating profit of $3,026/ha.

- Option 1: Covered Feed Pad investigated covering the current loafing pad near the dairy shed and a trough feed system put in place for the supplementary feeding of maize silage and PKE. The additional effluent generated fitted ithin the current system capacity, meaning there was little additional capital needed for this. An 8% increase in cows was modelled, along with a 5% increase in milk production per cow. The N balance dropped slightly to 95 kg/N/ha, with operating profit increasing by 12%.

- Option 2: Composting Barn added greater flexibility for management. This included feeding supplements, particularly during winter, and managing through adverse weather events. This saw the herd size able to be increased by around 8%, resulting in a 5% increase in production, while feed supplements stayed around the same. With a loafing pad already in place, production gains were not as great as had been previously modelled for other farms. The N balance dropped to 90 kg/N/ha, with operating profit increasing by 7%.

- Option 3: Diversifying System saw a reduction in the dairy herd size by 20%, along with an accompanying reduction in replacement animals, and the introduction of dairy-beef finishing on the farm rearing all calves through to 12–14 months. This saw lower production levels, but also lower staffing and input costs. The N balance dropped to 94 kg/N/ha, with operating profit down 11%.

No single best option

“From a financial perspective, combining forage crops with low-cost stand-off pads may be a better solution for some farms, while becoming self-contained, purchasing additional land and diversifying into beef may be harder to justify,” says Bunning.

“However, soil type and the downstream receiving environment need to be carefully considered to avoid environmental issues,” she says. Although not

quantified, previous research in Southland and Otago has shown sediment and E. coli losses can be reduced by two-thirds under better wintering practices (equal to a one-third reduction annually).

Covering feed pads would see improvements for animal welfare and reduce soil damage, with the ability to keep animals off-pasture for longer periods of time. But in areas that experience very high rainfall and serious pugging issues, the more expensive covered structures like herd shelters or composting shelters may be a better option.

“Many farmers were hoping for a definitive answer as to the best option for the Coast, but the research confirmed that the optimal solution is always location-specific,” says Curtis.

“As a result, the key output from this project has been a decision-making framework for farmers and their advisors. This includes consideration of landscape, catchment and animal welfare risks, farm system and management limitations, financial constraints and the goals of the farm owner” (see Figure 1).

This article was first published in New Ground magazine, issue 3. All text is licensed for re-use under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Author

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

View Our Strategy Document 2019 – 2024

Leave a Reply