Researcher profile: Tiffany McIntyre

Tiffany McIntyre loves farming. She grew up on a farm. Her grandfather and father were dairy farmers. And she wanted to go straight into farming after she finished high school.

Her parents suggested she have a look around and see what else was out there before making that decision and she ended up “falling in love with supply chains and marketing”.

That’s not as weird as it sounds.

“Studying supply chains opened my eyes to the fact that there are other ways to farm. You don’t have to just take what you're given. You can make money on your own terms, you can produce things in the way you want to produce them and make sure you’re looking after the environment and the people you’re working with.”

Most people only notice a supply chain when it doesn’t work. Like when there’s a ship stuck in the Suez Canal.

Even less well known is the difference between supply chains to their fancier cousin, the value chain.

“Creating a value chain means moving from a situation where a farmer has these specifications they have to meet and the product goes on its merry way, to creating a product that can connect with the consumer and extract a premium.”

— Tiffany McIntyre, AERU

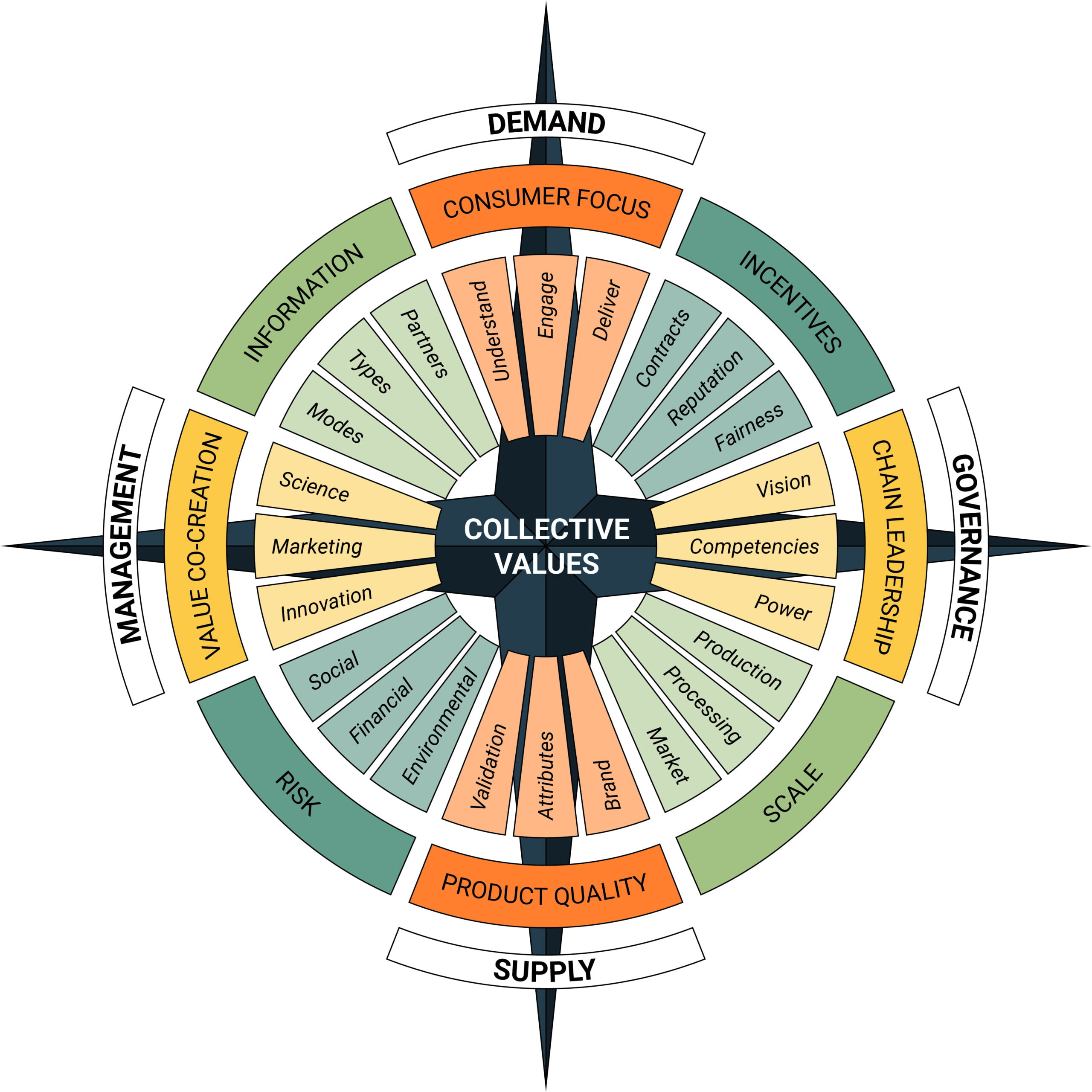

McIntyre, who is a research associate at the Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit (AERU), received funding as part of the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge to study successful New Zealand exporters. The study, Integrating Value Chains, followed up by Rewarding Sustainable Practices, identified nine attributes.

Values matter more

Collective values is one of the most crucial factors.

“Those nine attributes are like a wheel and the shared values are in the middle of that wheel. They are what helps it turn. Aligning with businesses that share similar values is really important.”

Focusing on what consumers want is another key component. Market research by the AERU shows that there is an upside for everyone when New Zealand producers sell premium products imbued with so-called ‘credence attributes’. These attributes are additional to taste and quality and include such qualities as animal welfare standards, carbon zero status, water quality or organic certification.

The market research by AERU shows that consumers in our key markets are demanding high sustainable standards, especially for premium produce. “You can’t go into a market without knowing who your customer is and what they are willing to pay. And then you need to make sure you back up your story with product quality.”

“Consumers want to know you’re doing the right thing, and if you can prove it, you earn trust, you help the environment and you get a premium. It’s a win-win-win.”

— Tiffany McIntyre, AERU

Producers of course are getting it from both sides: there’s growing regulatory and public pressure on growers to limit their impact on the environment. When McIntyre was growing up, big corporations were coming in and dictating what farmers could and couldn’t do. The strategy could be summarised as: more stock, more fertiliser, more water.

“I don’t think it’s fair to say to farmers you need to sort this out, but the consumer is putting pressure onto the firms to act in a certain way. The more they are aware of the environmental effects of farming, the more they can ask them to change.”

Some farmers see this as additional compliance. But McIntyre says it’s about the social licence to operate. And while she believes most farmers on the ground really want to make these changes, one of the constraints is that there has to be a balance between financial payoff and financial cost.

“The crucial bit is that you build that into your marketing. Consumers want to know you’re doing the right thing, and if you can prove it, you earn trust, you help the environment and you get a premium. It’s a win-win-win.”

From volume to value

Like her AERU colleague Professor Caroline Saunders, McIntyre has seen a shift in focus from volume to value since she started her academic journey in 2016, especially among smaller players who have the freedom to be more innovative. And she thinks these case studies provide a good model for other primary producers to follow.

“When it comes to the environment, many farmers are showing their own initiative rather than relying on legislation to dictate what they need to do, and that’s awesome. We do see a lot of innovation going on and a lot of farmers starting to diversify production, or find new types of production. We’ve got coffee beans up north, we’re growing bananas, we’re trialling peanuts. It's exciting to find out how these products all fit together and how we can sell them to the world – and get that premium back to our farmers.”

She says Ireland’s Origin Green initiative has provided a good example of how sustainability certification can benefit primary producers and environmental standards. While New Zealand’s positive perception around the world is certainly very important, the problem with relying on country-of-origin labelling is that it leaves companies vulnerable to “one bad apple souring the whole lot”.

“New Zealand has a good reputation, but there is a need to move away from that reliance. It’s important to have our own identity.”

Read more about Tiffany McIntryre’s work here

An instruction is not a plan: how to create value in the primary sector

Bill Kaye-Blake, principal economist with NZIER, reflects on 20 years of research into creating greater value in New Zealand’s primary sector. I’ve…