When Patsy Bass left high school, she had planned to go to university and become a kindergarten teacher. Her father talked her out of it and she eventually went on to forge a successful career in human resources and project management, after a brief foray into social work. She never imagined moving back to her hometown of Reefton, but she always wanted to make the West Coast rain sexy and creating a business that could help rejuvenate her hometown saw her return.

In brief

- Patsy wanted to start a business in her hometown Reefton to create sustainable jobs and to create a reason for people to visit and to stay

- She and husband Shane spent months talking to residents to identify what they liked, didn’t like and would like to see in the town

- It needed to be an authentic connection to Reefton’s past, while also with potential to create a modern tradition for the future

- It also references the pristine water sources and fresh native botanicals of the West Coast rainforest

- The story strongly connects with consumers who pay a premium for quality, authentic products with strong provenance

- Little Biddy gin quickly secured and has maintained the number two super-premium gin brand in New Zealand and the fastest growing

Bass and her husband Shane Thrower had no idea what kind of business they should set up there, so she held community forums, spent three months on the main street talking with visitors and locals, and even brought her professional network to the town to look at the different resources on offer and come up with a range of different business ideas that might work.

“Reefton Distilling Co. is a great example of using storytelling and sense of place to create emotional connections with consumers. People are prepared to pay a premium to participate in that authentic story. In terms of the Value Compass we regard Reefton Distilling Co. as a great example of Consumer Focus,” says Professor Paul Dalziel.

Bass also spent three months talking to people – locals and visitors alike – on the main street to find out what kind of business they wanted there and the main outtakes were that it had to be premium, and it had to be unique to the area, not just something that you could find anywhere in the world.

“People always had a negative mindset toward the rain in Reefton, which astonishes me. When we were growing up we never thought anything of it. We would just put on our gumboots and a raincoat and we did all the same things we would do if it was sunny. It never stopped us, and I see it as just a mindset. I love the rain, I find it invigorating. The wetter and wilder it is, the more likely you are to find me out walking or running in it. I wanted to make the rain sexy.”

What’s the story?

In her previous corporate roles, Bass says people were often told that if they could find something they were passionate about, they would never work a day in their life.

“I didn’t drink, so I wasn’t passionate about alcohol at all, but I was passionate about my hometown and everything was pointing towards a distillery,” she says, from the plentiful, pure water to the array of native botanicals in the surrounding rainforests, to the rich alcohol-soaked history of the area.

After local twins Nigel and Steffan MacKay (who are teetotallers, having never touched alcohol in their 74 years, and are now the company’s head foragers and brand ambassadors) told Bass they were looking at buying a building to open a museum for their large collection of whisky vessels, the final piece fell into place. Reefton Distilling Co. was established in April 2017 and opened the doors in October 2018.

“What really resonated with people is that we set out to create jobs and a tourist attraction. It was never about making swags of money for Shane and me. It was about creating something that would revitalise the town, inspire others with what is possible on the West Coast and knowing our parents, who loved this town, would be so proud.”

And, ironically enough, she says “running a business can be a bit like being a kindergarten teacher some days!”

Demand curve

Lincoln University’s Agribusiness and Economic Research Unit (AERU) conducts surveys to identify the premium buyers will pay for products with intangible ‘credence attributes’ like lower environmental impacts, good animal welfare or worker welfare standards, organic status or, in the case of Reefton Distilling Co., regional and brand authenticity. This provides a justification for producers to cater to that demand and, as the case studies for The Value Project show, this means it is possible for savvy New Zealand food and fibre businesses to produce less and earn more, while limiting their impact on the environment.

“We talked to a distributor at concept, told them the price we were aiming for and they said ‘you won’t sell any in New Zealand at that price’. Initially we were only going to do really high-priced items, so we brought it down to $84.99 and they still said it was at the top of the market and you wouldn’t sell much.”

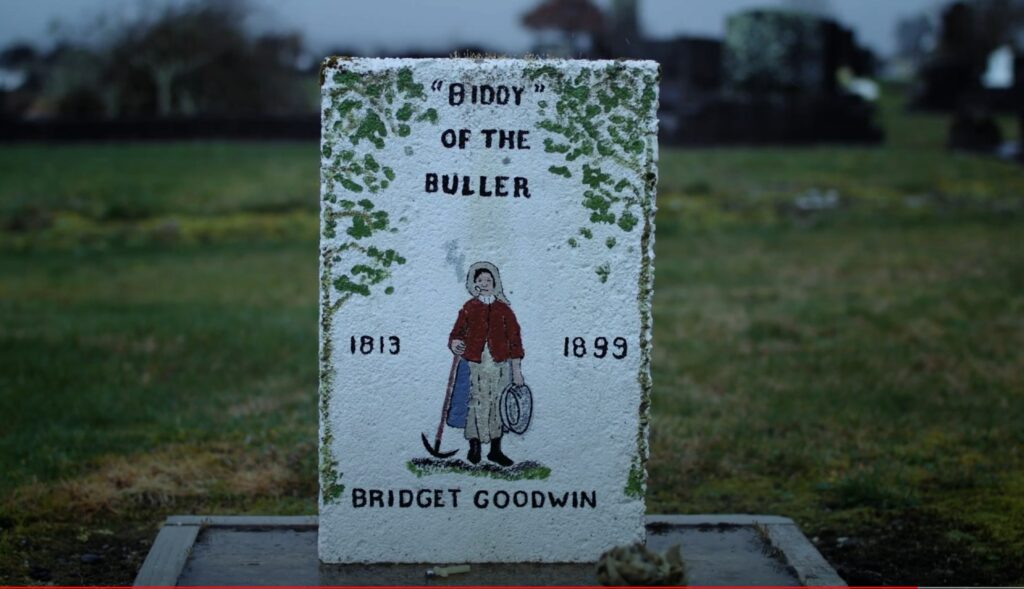

Some in the Reefton community were also sceptical that people would spend that much on a bottle of Gin. But as Steve Jobs said, people often don’t know what they want until someone gives it to them and, as business professor and podcast host Scott Galloway writes, brand is Latin for ‘irrational margin’, so consumers will often pay much more for a product that they have an emotional connection to. That is what Bass tried to create from the start and shortly after launching Little Biddy Gin, which was named after “a gin-toting, 4-foot tall, Irish female gold prospector”, it became the number two gin in New Zealand and retains that position.

Rising above the rest

When they started, she says there were 35 registered and/or gin brands in the country. Now there are about 150, although many simply contract out their manufacture.

“New Gin brands are popping up almost weekly.”

She likens it to venison or honey businesses that were established when the market was hot.

“But a lot of [spirits makers] can’t be earning a living off their product and might be doing it on a tiny 10 or 50L still in the garage. It’s incredibly difficult to them to get shelf space in stores because it’s so congested now. That’s why we went out and did the capital raise [over $1 million in 2018 and another $3.3 million in 2020, $4m in 2021 and with a $925,000 provincial growth fund loan toward their larger new distillery]. Instead of doing it at our own pace, we went bigger earlier to establish our brand before the category was saturated.”

She says the story behind the business has played an enormous role in establishing that name, both in terms of attracting domestic and international customers and getting distribution. You’re drinking what you’re thinking, after all, and, for Bass, their products, which also include Wild Rain Vodka, Flavour Gallery Gin Series and a range of fruit liqueurs, are a literal and figurative distillation of the West Coast and everything it stands for.

“People came to us because of the story. Ballantynes [the iconic department store in Christchurch] can be really hard to get into, but we were fortunate as they approached us. They had heard about what we’re doing, loved the provenance, social responsibility and brand story, and they are still big supporters.”

“It seemed every journalist in the country” wanted to hear our story and either still had family on the West Coast, or had some special memory or connection to the region”. The pandemic led to understandable delays in the opening of the new distillery but, on the plus side, with all those captive Kiwis, online orders went absolutely ballistic and the increase in domestic tourism saw plenty of travellers visiting Reefton to sample their wares.

A big part of the appeal, Bass says, is that the story isn’t made up. It’s authentic, it’s creating significant employment in the town of 900 and they’ve made products that are unique to that particular place and are inspired by its history. If they were making gin in an industrial estate in a major city, just contracting it out and then manufacturing the story, it just wouldn’t work, she says.

“One of the marketing experts I brought over to Reefton said ‘why the hell are you wanting to create a business there?’ He thought I was mad. But when he got here, he was beside himself. He said “usually we’re casting around to try and create a story to fit behind a brand, but here there are so many good stories – the problem is which one to choose!’”

And good stories tend to spread. Bass says they’ve been in restaurants in the city and waiters have recommended “this really great gin from the West Coast and share the story of native botanicals, awards and the jobs the distillery is creating in a small rural town.” (Bass –a reformed non-drinker, now has the occasional G&T – for quality control, of course).

“And we say ‘that’s our distillery!’ with enormous pride. It’s really cool to see how wide it’s gone.”

Onwards and upwards

Despite the success, Bass knows it can go a lot further, both in New Zealand and overseas.

Reefton Distilling Co. has worked closely with NZTE, which has provided data and expertise for their entry into offshore markets and the company sells in the UK, has recently found a distributor for the Australian market after a successful D2C pilot and is in discussions with several other markets.

At this stage, Little Biddy Gin – Classic and Pink are available in Australia and the distributor will up to 18 months seeding the market before introducing other products. While Australia is also congested and a strong supporter of Australian made, Bass is confident the company can harness the positives of the Pure New Zealand brand to get a foothold in the market and maintain their premium. And of course, there are a lot of Kiwis living in Australia. At the time of going to print, their Australian distributor had already been in touch to take their new Flavour Gallery Gin Series, so things seem to be heading in the right direction.

“The West Coast doesn’t mean much outside of New Zealand,” Bass says, so once we move offshore we switch that out for New Zealand.”

Regional differences can increase the price of certain products if there is a solid reputation for quality or uniqueness. Sometimes it’s legally protected, like Champagne or Feta, sometimes it is imbued into the marketing, like Beef + Lamb’s Taste Pure Nature campaign.

With “world-class grain grown on our doorstep in Canterbury” and all that plentiful, pristine water, Reefton Distilling Co. is also making a New Zealand single malt whisky. The first will be released to market in 2025-26. The whisky is named after George Fairweather Moonlight, a legendary gold prospector who discovered the field of New Zealand’s largest gold nugget, and Reefton Distilling Co. have brought in two experienced Scottish Master Distillers to help produce it and they have an international panel of whisky specialists overseeing its development.

“The Scots don’t mind the rain,” she says. “They’re pretty comfortable in these conditions.”

In the world of spirits, she says Scotland is a good model for what could be achieved on the West Coast, she says, in terms of creating employment around distilleries, getting a premium for the products and attracting visitors to far-flung (often climatically challenged) locations.

Just as the smartest players in the agricultural sector are trying to escape the commodity trap, the tourism industry is also looking to reorient itself towards higher value tourists. And those two areas are linked, because a 2018 report from ANZ and MPI on the potential of food and agri tourism and its link to increased trade showed that food tourists should be a primary target.

Research at the time suggested those who travel primarily for food and beverage experiences spend 50% more on food and beverage per day when travelling compared with other leisure tourists. Visitors to New Zealand who visited a vineyard or attended a wine event spent over 25% more on their trip than the average spend. And the lasting benefit of food tourism is that when visitors return to their home countries, “over 60% of travellers purchase food and drinks that they first encountered on a trip”.

Bass says a huge number of visitors to Reefton now stop at the distillery and, as hoped, it has been a catalyst for improvements to the town, with other entrepreneurs now seeing potential there. She’s confident that momentum will continue to build and more diverse food outlets will open, more accommodation will be built for those who want both visit and choose to live there and there will eventually be “less of the boom and bust we’ve seen associated with mining”.

Liquid legacy

Bass is proud of what she and her team have achieved so far. The business has created 25 jobs and pumped millions of dollars into the local economy in the form of wages, building/trades and tourism. A recent capital raise allowed the distillery to buy a 1.6 hectare plot of land (with buildings) in Reefton and production has now relocated to the site.

“We now need to regenerate the site. It was a dairy farm and then a contractor’s yard, which we’ll plant with our native botanicals so we can forage from our own garden and show visitors what e.g. a Rimu or Toatoa tree looks like, or a Tayberry.”

In five years, she hopes the current site will be completely developed and they will have doubled the number of jobs.

The West Coast has always been a place that attracts interesting, hardy, entrepreneurial characters. Reefton Distilling Co. has unearthed some of those characters and they’ve inspired their marketing, and Bass is continuing that tradition.

As it says on the website: “There is something about the spirit of the West Coast and its people. They have always had belief in themselves, a can-do attitude and they are not afraid to get behind a new idea. Reefton was an entrepreneurial and prosperous place in its early days, and we in turn plan to add the success of Reefton Distilling Co. to the history books.”

Cheers to that.

Ben Fahy is a freelance writer specialising in business and sustainability. Read more about value creation in New Zealand food and fibre sectors at The Value Project

An instruction is not a plan: how to create value in the primary sector

Bill Kaye-Blake, principal economist with NZIER, reflects on 20 years of research into creating greater value in New Zealand’s primary sector. I’ve…